How to Escape the Labyrinth of Your Own Mind?

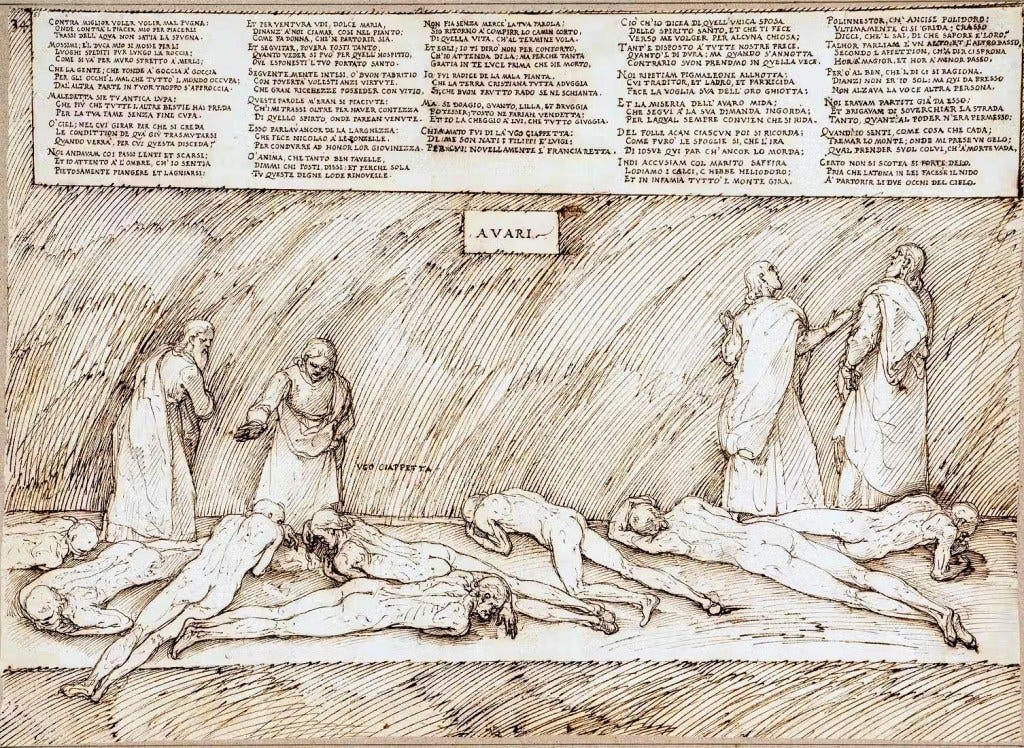

(Purgatorio, Canto XX): Hugh Capet, avarice

There were many minds who remained free in physical prisons, but none that escaped confines of a mental one.

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! ✨

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

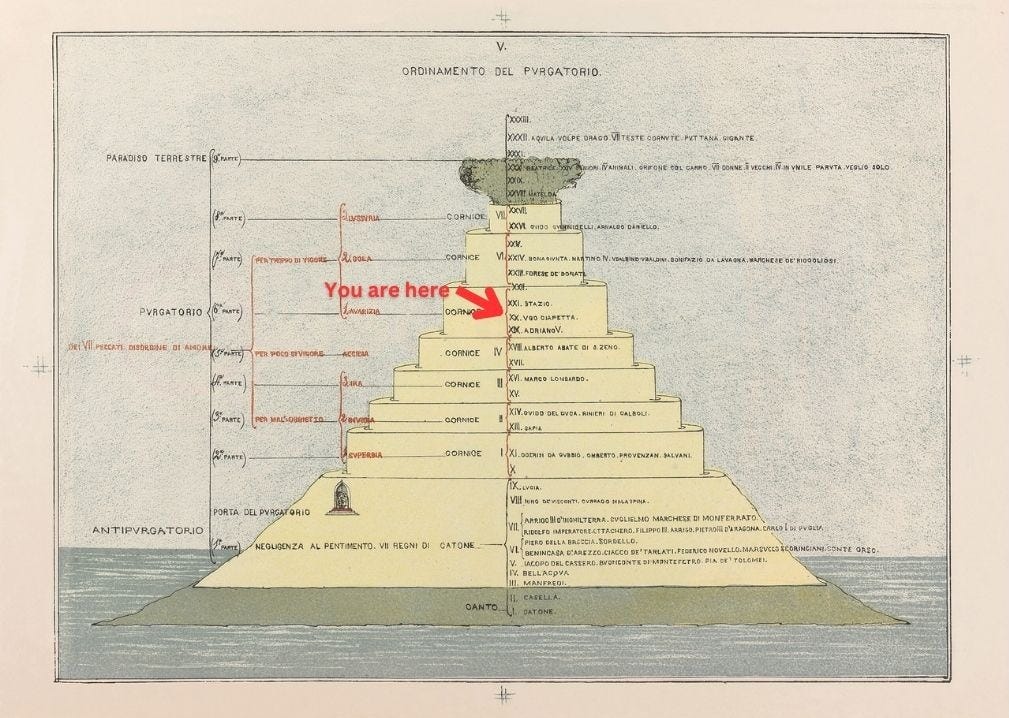

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Nineteenth Canto of the Purgatorio, Dante dreams of the Siren. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

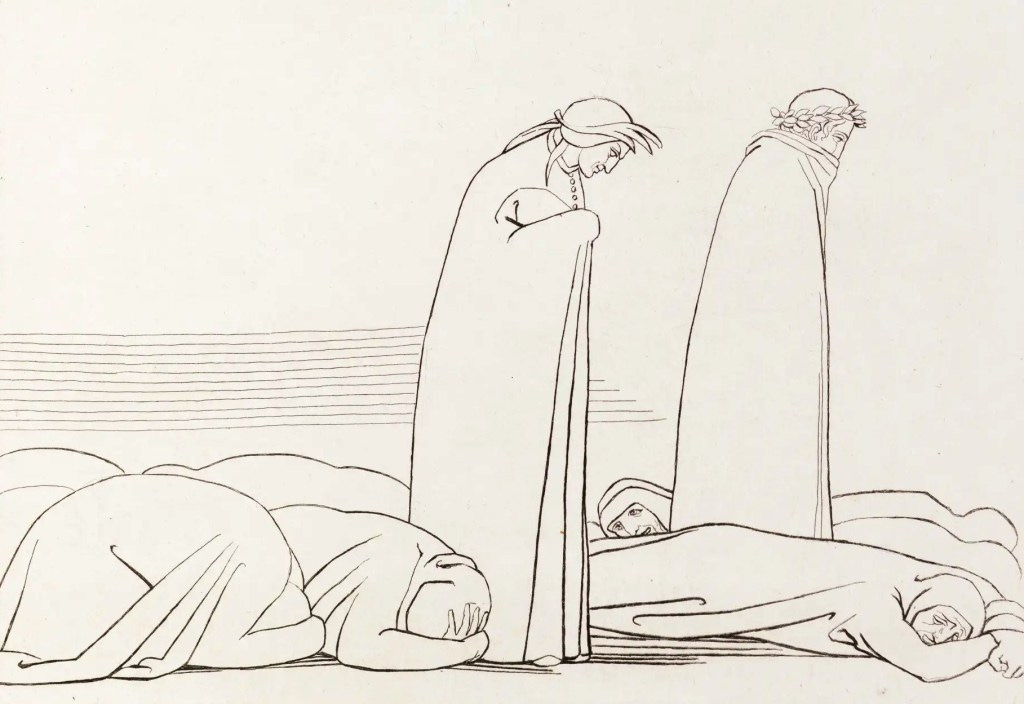

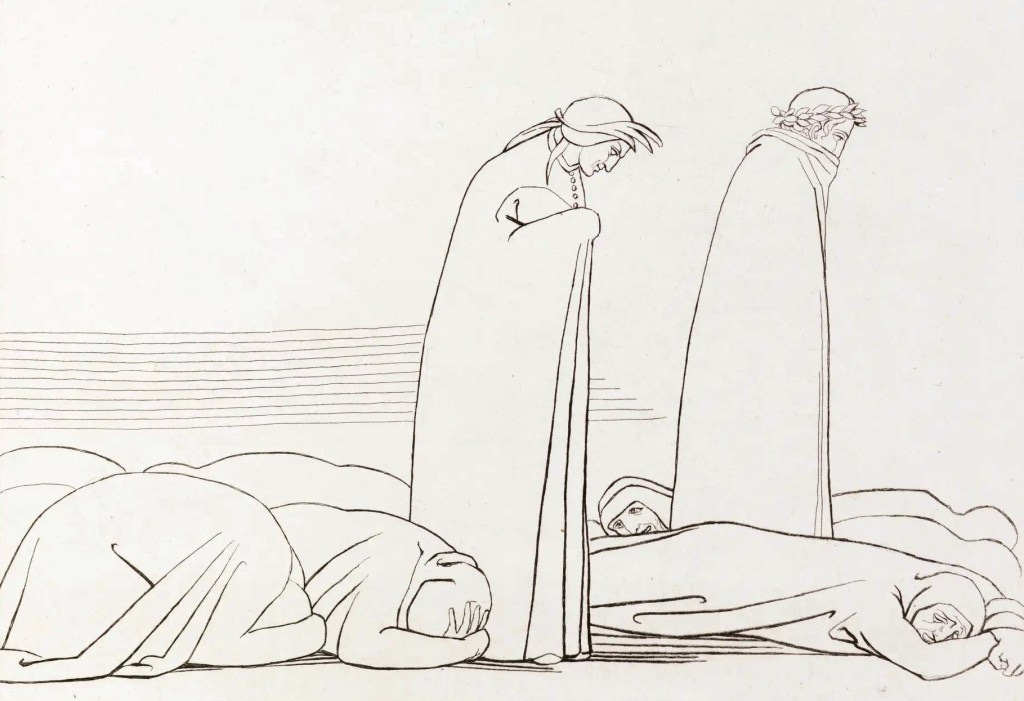

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Fifth terrace of Avarice - Exemplas of poverty - Mary, Fabricius, and St. Nicholas - Hugh Capet and the lineage of French kings - The avarice of the Capetians - Condemnations of Avarice - Pygmalion, Midas, Achan, Sapphira, Heliodorus, Polymnestor, Crassus - The trembling of Mount Purgatory - Gloria in excelsis Deo.

Canto XX Summary:

Dante honored the “better will” of Pope Adrian V to return to his penance, even though he was left with so many questions to ask, and ready as he was to absorb their answers as an “unquenched sponge” (3). Dante and Virgil continued along the fifth terrace of Avarice, carefully making their way amidst the recumbent souls lying face down in the dust, tightly along the inner edge along the wall of rock to their right. The penance of these souls was being shed from them like water dripping from ice:

For those whose eyes would melt down, drop by drop,

the evil that possesses all the world,

were too close to the edge, on the far side.

xx.7-9

The crowded nature of this terrace points to how prevalent this sin was in the world of the living; in the Inferno, the most crowded ring were of those Miserly and Prodigal who misused their wealth,1 mirroring these repentant Avaricious.

Just as avarice possesses the whole world, these souls ‘occupy’ the whole terrace, as the following verse indicates. It will be remembered that there was also stress on the great numbers of the avaricious in their respective circle in Hell.2

Here in full force are those who suffered from the sins of the she-wolf of the very first canto of Inferno, the “most troublesome of the three beasts”3

And then a she-wolf showed herself; she seemed

to carry every craving in her leanness;

she had already brought despair to many.

Inferno i.49-51

This nature of avarice claimed more souls than any of the others sins and vices; also referenced is that Greyhound, the only one who could chase away the wolf.

May you be damned, o ancient wolf, whose power

can claim more prey than all the other beasts-

your hungering is deep and never-ending!

O heavens, through whose revolutions many

think things on earth are changed, when will he come-

the one whose works will drive that world away?

xx.10-15

The prophetic question looks to the advent of that temporal monarch about whom Dante composed his treatise De monarchia, the same that was called the ‘veltro’ in the first canto of the Inferno and whose birth (i.e. advent) was to be ‘between felt and felt’, that is, under the sign of Gemini.4

Dante’s mind was filled with thoughts of the extent of the suffering of the shades, when a voice cried out as if in the travails of birth, calling out the exemplas that opposed Avarice; those virtues that were types of generosity and voluntary poverty. First, as always, was an aspect of Mary, who demonstrated voluntary poverty in the willingness to give birth in a stable in Bethlehem.

The second example came from voluntary asceticism, as practiced by Gaius Fabricius Luscinus, Roman consul and censor. He refused to partake of the plunder of Roman enemies, attempted to reign in the luxurious excess in Roman government, and even in his high position, died in poverty; Virgil said of him that he was a man “great with little means.”5

Did not Fabricius give us a lofty example of resisting greed when, in the fidelity that held him to the Commonwealth, poor as he was, he scoffed at the great pile of gold offered to him, and having scoffed thereat and uttered words worthy of himself, contemned and refused it? Dante de monarchia II.v.11

The last example was that of generosity to the poor in the figure of St. Nicholas (who has been transformed into our modern Santa Claus), the fourth century bishop of Myra in Asia Minor.

At the time a certain fellow townsman of his, a man of noble origin but very poor, was thinking of prostituting his three virgin daughters in order to make a living out of this vile transaction. When the saint learned of this, abhorring the crime he wrapped a quantity of gold in a cloth and, under cover of darkness, threw it through a window of the other man’s house and withdrew unseen. Rising in the morning the man found the gold, gave thanks to God, and celebrated the wedding of his eldest daughter. Not long thereafter the servant of God did the same thing again. This time the man, finding the gold and bursting into loud praises, determined to be on the watch…some time later Nicholas threw a double sum of gold into the house. The noise awakened the man and he pursued the fleeing figure…until he saw that it was Nicholas. Falling to the ground he wanted to kiss his benefactor’s feet, but the saint drew away and exacted a promise that the secret would be kept until after his death.

Jacobus de Voragine, Legenda Aurea 21-22

The soul who expressed these exempla was as yet unknown, and Dante asked him two questions; who he was, and why he spoke out the virtues by himself, and not in chorus? He made the oath so familiar to us now, to be of help to the penitent’s soul back on earth if possible.

And he: “I’ll tell you-not because I hope

for solace from your world, but for such grace

as shines in you before your death’s arrived.

I was the root of the obnoxious plant

that overshadows all the Christian lands,

so that fine fruit can rarely rise from them.

xx.40-45

We have met Hugh Capet, he who gave birth to the dynasty of the House of Capet in the lands of France, which lasted over 300 years to find its culmination in Dante’s day with Charles of Anjou. Just as his voice called out as in the travail of birth the names of the exempla of poverty, as king he birthed a long and ignoble house.

The metaphor here draws on the image of a real tree, bearing the suggestion that it has now grown so tall that it casts its shade over all Christendom, a shade in which good fruit can rarely be produced.6

By putting such a grave condemnation of that house in the mouth of its founder, Dante means to give it the quality of absolute truth, just as he did when he had the Romagnoles condemned by a Romagnole, and the Lombards by a Lombard.

M. Porena, La parola più misteriosa della Divina Commedia.

The speaker is Hugh Capet, founder of the Capetian dynasty of the kings of France, which, by alliance, inheritance, or conquest, exercised a dominating influence throughout Europe for some two and a half centuries. Many of Dante’s most virulent hatreds attach to members of this family.7

After the simile of the tree, Hugh Capet spends the next 17 tercets expounding upon his lineage and the occasions of their avarice, giving an in depth look at the descendants of his line, and his prophecies about those that are contemporary with Dante. However, the accuracy of some of Capet’s statements leave students of history at a loss in untangling their claims. I will share what some of the best commentators have concluded about the historicity of Hugh Capet’s speech.

The statements put by Dante into the mouth of Hugh Capet as to the origin of the Capetian dynasty are in several respects at variance with the historical facts and can be explained only on the supposition that Dante (as common tradition before him) has confused Hugh Capet with his father, Hugh the Great, some of the statements being applicable to the one, some to the other.8

The rulers of France who had come after him were, to a man, all named either Louis or Philip, but the father of humble origins whom he points to, the butcher, had been widely believed—but in error—to be the father of Hugh the Great.

Hugh continued on, pointing to his own son as becoming the first crowned member of the family, when in fact, it is himself who is that first king. The scheme of his descendants to obtain the dowry of Provence was the real beginning of his house’s downfall, when Charles of Anjou—brother of the King of France—married Beatrice, the heiress of Provence, who had been promised to another.

With irony, Capet told Dante that, “to make amends,” those of his house seized lands belonging to English rule—Ponthieu, Normandy and Gascony; then Charles of Anjou defeated the rightful heir of Naples and Sicily, Conradin, and lastly, the rumor that Charles had ordered the poisoning of St. Thomas Aquinas (of whose philosophy we read so much in Virgil’s discourse on Love).

Hugh prophesied another Charles, this one Charles of Valois, who looked peaceful, yet with his treacherous lance instigated the events that would lead to the expulsion of the White Guelfs from Florence, of which Dante was one.

The third Charles of whom he prophesied was Charles of Anjou II, whose avarice shone through his actions of marrying off his daughter to Azzo VIII, a much older man, for a generous sum; Hugh lamented that his descendants were enslaved to avarice, and cared more for gain than their own families.

Nothing in Dante is more paradoxical or more magnificent than his treatment of Boniface VIII. Of all his enemies, personal and political, none is so hateful to him as Boniface. Yet, stained with simony, with murder, with treason, with the rape and robbery of the Church and the ruin of the Empire, he see usurped, so that it now stands ‘vacant in God’s Sons sight’; nevertheless, Christ’s Vicar is Christ’s Vicar still, identified with Him in the sacrament of his anointing; and to lay hand on him is to crucify Christ afresh. This balance of two equal and opposed indignations, both blazing, and mutually unmitigated, is a triumph of the passionate intellect unsurpassed in literature and scarcely paralleled.9

I see Him mocked a second time; I see

the vinegar and gall renewed-and He

is slain between two thieves who’re still alive.

And I see the new Pilate, one so cruel

that, still not sated, he, without decree,

carries his greedy sails into the Temple.

xx.88-93

Through Philip the Fair, this ‘new Pilate’, Dante exclaimed that Boniface was treated no better than Christ himself in the drama of his crucifixion. For calling for excommunication of Philip, he was kidnapped and beaten, and died shortly after being released. To add to his list of insults, Philip the Fair was also the one who brought about the destruction of the Knights Templars.

Hugh Capet had finished relating his lineage to Dante, and moved on to Dante’s second question proposed in lines 35-36: why was he alone in his calling out of the exemplas of poverty when they first came across him?

What I have said about the only bride

the Holy Ghost has known, the words that made

you turn to me for commentary-these

words serve as answer to our prayers as long

as it is day; but when night falls, then we

recite examples that are contrary.

xx.97-102

Hugh went on to name seven examples of the bridle of Avarice from classical and biblical sources, beginning with Pygmalion, the brother of Queen Dido in the Aeneid, who had murdered her husband, Sychaeus, precipitating her flight from Tyre to found Carthage:

Ruling Tyre, in those days, was Pygmalion. He was her brother,

And quite a monster of crime, far surpassing all possible rivals.

Conflict arose among in-laws. Pygmalion, secure in his sister’s

Love for them both, lusting blindly for gold, killed Sychaeus in cold blood

Secretly, catching him quite off guard and in front of an altar.

Evil, unrighteous man, he concealed what he’d done for a long time,

Toyed with the lovesick bride, raised false hopes, crafted illusions.

But in her dreams, the true form of her unburied husband approached her,

Raising before her a face that was wasted with terrible pallor,

Baring the truth of the brutal crime at the altar, the daggered

Breast, and disclosing each unseen crime concealed in the palace.

Virgil Aeneid i.346-356

Next was Midas, the Phrygian king, who, upon doing a favor for Bacchus, was granted a wish. He wished that anything his body touched would be turned to gold, and learned quickly what a terrible request it was. He begged to remit his mistake:

Astounded by this strange catastrophe

of wretchedness in wealth, he longs to flee

its trappings-now despising what he’d prayed for.

Abundance was unable to relieve

his empty stomach or his burning throat;

so justly tortured by the hateful gold,

he raised his hands and gleaming arms to heaven:

“O Father Bacchus,” he cried, “show your favor!

Though I have sinned, I beg you, grant me mercy,

save me from this ruinous extravagance!”

Ovid Metamorphoses ii.177-186

The wish was retracted; but there was more to the story, that “consequence that always makes men laugh” (108). After the saga of the golden touch, Midas was asked to judge a musical contest between Pan’s pipes and Apollo’s lyre; Midas voted for Pan, and as a punishment from Apollo was given the ears of an ass.

Achan was next, a figure from the book of Joshua in the Hebrew Bible; he hid thefts from the fallen city of Jericho when all were commanded to take nothing for themselves; because of his deceit, the upcoming battles they fought were lost, and when he confessed, he and his family were put to death by stoning.

And Joshua, and all Israel with him, took Achan the son of Zerah, and the silver, and the garment, and the wedge of gold, and his sons, and his daughters, and his oxen, and his asses, and his sheep, and his tent, and all that he had: and they brought them unto the valley of Achor. And Joshua said, Why hast thou troubled us? the Lord shall trouble thee this day. And all Israel stoned him with stones, and burned them with fire, after they had stoned them with stones. And they raised over him a great heap of stones unto this day.

Joshua 7:24-25

Sapphira was another biblical example from the New Testament; when she and her husband Ananias hid money from the sale of land that was to go to the church, they were struck dead; first Ananias, and later, Sapphira.

Heliodorus, treasurer of the king of Syria, attempted to sack the temple at Jerusalem and steal its treasures; he was attacked by a divine rider on a magnificent horse:

For there appeared to them a magnificently caparisoned horse, with a rider of frightening mien; it rushed furiously at Heliodorus and struck at him with its front hoofs. Its rider was seen to have armor and weapons of gold. Two young men also appeared to him, remarkably strong, gloriously beautiful and splendidly dressed, who stood on either side of him and flogged him continuously, inflicting many blows on him.

2 Maccabees 3:24-26

Polydorous, the son of Priam, king of Troy, was placed, along with treasure, with Polymnestor for safekeeping during the Trojan War; Polymnestor betrayed Priam’s trust, slew Polydorous, and stole the money; we saw his tale from the point of view of his mother Hecuba.10 And finally, the voice of the Parthian king jesting over the beheaded Crassus:

Marcus Licinius Crassus…was consul with Pompey in 70 B.C. and triumvir with Caesar and Pompey in 60. His ruling passion was the love of money, which he set himself to accumulate by every possible means…he was defeated and killed by the Parthians, who cut off his head and sent it, together with his right hand, to the Parthian king, in token of their victory, who then had his mouth filled with molten gold in mockery of his passion for money.11

Hugh Capet continued to explain to Dante their evening recital of these bridles of Avarice, and why it seemed that Dante heard only one voice.

At times one speaks aloud, another low,

according to the sentiment that goads

us now to be more swift and now more slow:

thus, I was not alone in speaking of

the good we cite by day, but here nearby

no other spirit raised his voice as high.

xx.118-123

At this, they left Hugh Capet behind, but as they continued on their way, the mountain shook violently, leaving Dante numbed and fearful; from all around came voices shouting, and as Virgil comforted Dante in his fear, the words Gloria in excelsis Deo rang about them, the same angelic song that announced the birth of Jesus to the shepherds in the nativity; they stood listening, until both the hymn and the shaking ceased. Never had Dante been as thirsty for truth as he was at that moment, so much did he desire to understand what had just occurred:

My ignorance has never struggled so,

has never made me long so much to know—

if memory does not mislead me now—

as it seemed then to long within my thoughts;

nor did I dare to ask—we were so rushed;

nor, by myself, could I discern the cause.

xx.145-150

With these thoughts, they continued on their way.

💭 Philosophical Exercises

Genuflection before the idol or the dollar destroys the muscles which walk and the will that moves.

~ Victor Hugo

Often, we must walk the full length of the labyrinth before we learn where we should have turned.

Our journey through the Divine Comedy began in a dark forest. My reader may recall that when Dante first tried to ascend the hill toward the divine light, he was blocked by three beasts.

The most dreadful of them all, the one who devoured anyone who crossed her path, was the she-wolf, the embodiment of greed and avarice. Fifty-four cantos later, here in Purgatorio, we meet her again:

May you be damned, o ancient wolf, whose power can claim more prey than all the other beasts— your hungering is deep and never-ending!

The sin of avarice, in contrast to other sins, is dynamic, insatiable, never-ending. The avaricious we met in the Inferno were set to a Sisyphean task of rolling boulders up and down the hill endlessly. This terrifyingly profound Dantean contrapasso reveals the infinite appetite of greed, and the disordered economy of love that has gone beyond repair. So profound is their corruption that Virgil withholds even a single name from among the damned avaricious.

We might think of greed as an excessive love for money, for gold, for the endless hunger to add more zeros to what we already possess. But for Dante, avarice is a far deeper affliction. It’s not merely about wealth; it’s a spiritual disease, a disorder of love.

Do you remember Plutus, the demonic guardian we meet among the avaricious in the Inferno?

He’s the only figure we encounter there and he doesn’t even speak intelligibly. His broken, guttural cry is not language, but a collapse of meaning itself. This tells us something: that in the grip of avarice, even speech and even our physical body, crumbles.

Avarice resembles a labyrinth, you move through its winding paths without ever hitting a dead-end, and so you’re fooled into thinking you’re on the right track. But the farther you go, the more exhausted you become, until the dreadful truth reveals itself: this maze has no centre, no prize, no end. Only motion without meaning.

In the previous canto, we met Pope Adrian, not guilty of hoarding gold, but of a subtler vice: the ambition to climb ever higher up the “career ladder.” He was already the vicar of St. Peter on earth, and yet he still remained unsatisfied.

Here we meet Hugh Capet, whose family line aims to endlessly expand their domain, not knowing where their borders end, and the others’ begin.

I was the root of the obnoxious plant that overshadows all the Christian lands, so that fine fruit can rarely rise from them.

In the Inferno, the avaricious were condemned to push great boulders uphill, only to clash at the summit and repeat their punishment endlessly. As they reached the peak, they hurled blame, never at themselves, always at the world. Their labyrinth has no exit, because they never turned inward. They remained lost, not because of the maze’s design, but because they refused to question their own direction.

To escape the maze of avarice which, in some measure, afflicts us all, we must first stop moving. We must stand still. Not to examine the walls to our left or right, but to examine the self. Often, the real labyrinth is not outside us, but within.

II. Escape the labyrinth within

So, how do we escape the endless, aimless labyrinth of avarice within?

In Purgatorio, the avaricious are no longer condemned to movement. Unlike their counterparts in Inferno, who were doomed to ceaselessly roll boulders—mechanically, bureaucratically, without rest: here, they lie face-down in humbling stillness.

The lesson is clear: if the labyrinth leads nowhere, why exhaust yourself running through it?

They say that those who have lost themselves in the forest, first must stop, for continuing to wander aimlessly gets you deeper into trouble.

In this terrace of the avaricious we hear: “My soul cleaves to the dust.” Those who loved the gold and the comfort of a throne now must clench dust, re-learn how to enjoy it, as a child who does before they get spoiled by toys.

For too often, our palette is dulled by the overly saturated flavours we consume, until we forget what natural tastes feels like. Even water, an element essential to our bodies, begins to feel foreign to the tongue.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

I. The Division of this Canto

This canto - like every canto in the Comedy - is unique in its structure. Up until now, we’ve followed a consistent rhythm: first, examples of virtue to imitate; then, conversations with the souls; finally, counter-examples of the vice being purged.

But here, all three layers are woven into a single movement. We meet Fabricius, the Roman statesman renowned for his virtue during the Pyrrhic War. Then we hear from Hugh Capet, and finally, we witness the counter-examples, like Pygmalion, whose stories reflect the corruptive pull of earthly greed.

This compression of structure - virtue, reflection, and vice all in one - raises a question: does earthly avarice require a deeper form of purification? One so pervasive and insidious that it demands a more concentrated confrontation?

II. Pygmalion and Midas

One simply cannot pass over this canto without pausing to consider the rich cast of characters mentioned within. Among them, the stories of Pygmalion and Midas stand out as especially fascinating.

Pygmalion was king of Tyre and notably, the brother of Dido (yes, that Dido, the tragic queen who fell in love with Aeneas). Dido’s husband, Sychaeus, possessed a great fortune in gold. This wealth, however, sealed his fate: he was treacherously murdered by Pygmalion, who coveted it.

But the story doesn’t end there. Sychaeus appeared to Dido in a dream, revealing both the truth of his murder and the secret location of his hidden treasure. Dido, grieving yet resolute, took her late husband’s gold and fled to North Africa, where she would go on to found Carthage, thus depriving her brother not only of the treasure, but of the legacy he sought to control.

Another story we encounter in this canto is that of King Midas. Most of us are familiar with the tale of the cursed king who, to his ruin, turned everything he touched into gold. But there’s a striking detail, often overlooked12, that deserves our attention: this curse was bestowed upon Midas by Bacchus (or Dionysus), the god of intoxication, ecstasy, and madness.

As Hollander points out, Dante may also be alluding to a lesser-known episode in Midas’s mythology, the musical contest between Pan and Apollo. In this tale, Midas sides with Pan, favouring his rustic pipes over Apollo’s lyre. Offended by Midas’s poor judgment, Apollo punishes him by transforming his ears into those of an ass.13

III. Earthquake

At the end of this canto Dante and Virgil experience an earthquake that makes Dante shudder. I found this to be an incredibly powerful scene, which, as we soon will find out, means the ascent of a soul from Purgatory to Paradise. While it is incredibly hard to put into words, but doesn’t every inner transformation resemble an earthquake?

(It is also here, in Virgil’s words, that we hear that a soul gets purified only for the vice it was guilty of. In other words, one does not need to ascend through all the terraces, but must be purified for the specific sin (vice) they were guilty of)

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

At times one speaks aloud, another low,

according to the sentiment that goads

us now to be more swift and now more slow:thus, I was not alone in speaking of

the good we cite by day, but here nearby

no other spirit raised his voice as high.~ 118-123

Here, more than elsewhere, I saw multitudes / to every side of me—Inferno vii.25-26

Charles S. Singleton, Commentary on Purgatorio 469

Singleton 469

Singleton 470

Dorothy L. Sayers Purgatory 228

Singleton 474

Sayers 229

Singleton 476

Sayers 231

Inferno xxx.13-21

Singleton 494

As it often is… the most striking details are hidden in the plain sight.

Are those of us who prefer vulgar and cheap music or art resemble Midas? Do we prefer Pan over Apollo? Do our ears resemble the ears of an ass, but we fail to see it?

Can tell you honestly that I did not expect an encounter with the Capetian dynasty. 🙂

I love Gustave Dore as an illustrator. Such depth to his work/art. Also that labyrinth that is outside us and inside us. What a great metaphor for life. I think about labyrinths often. Slowing down and taking time to notice what is around us sure helps. Thank you as always for sharing your reflections!