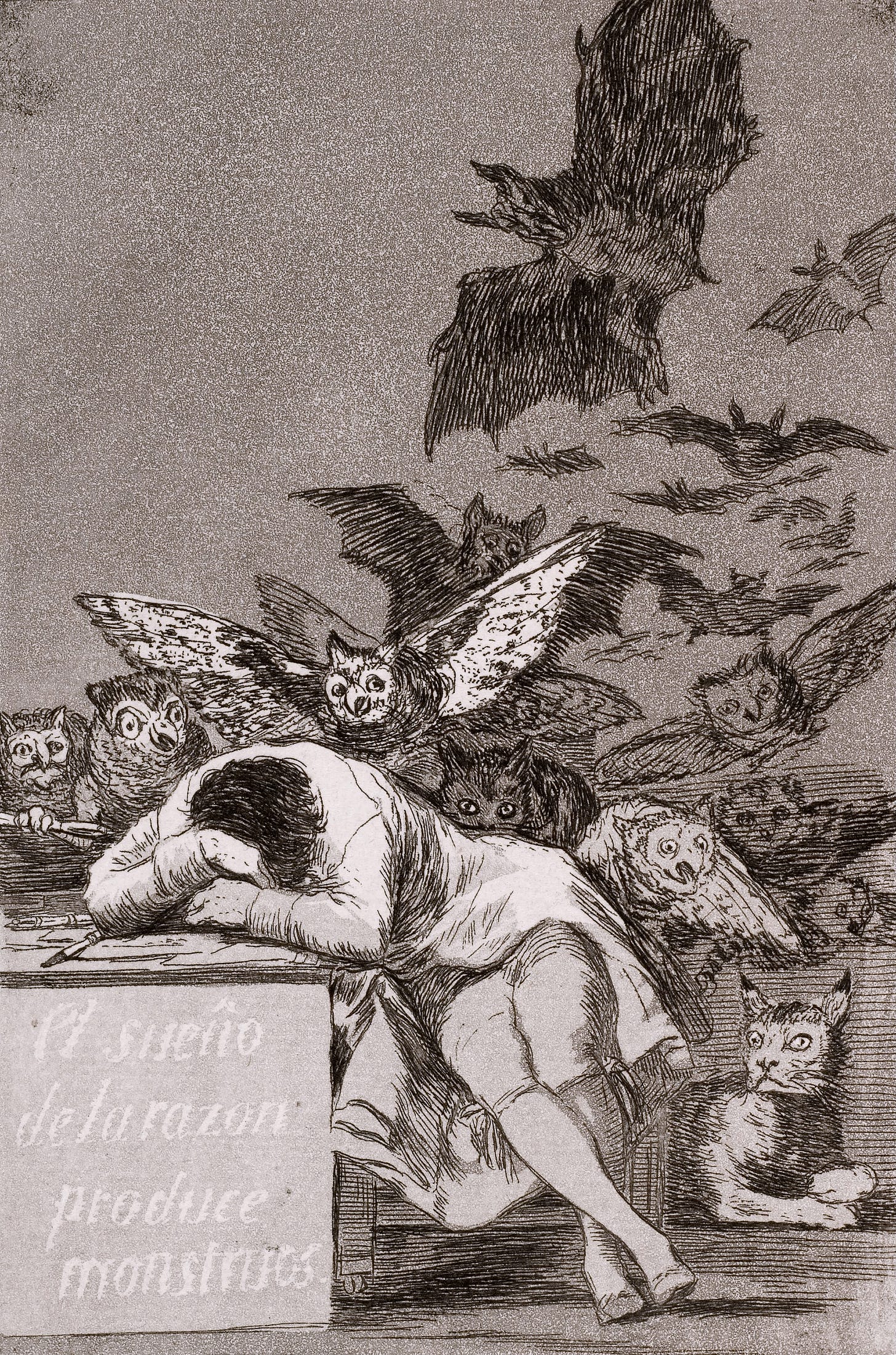

The Story Begins: The Sleep of Reason Creates Monsters

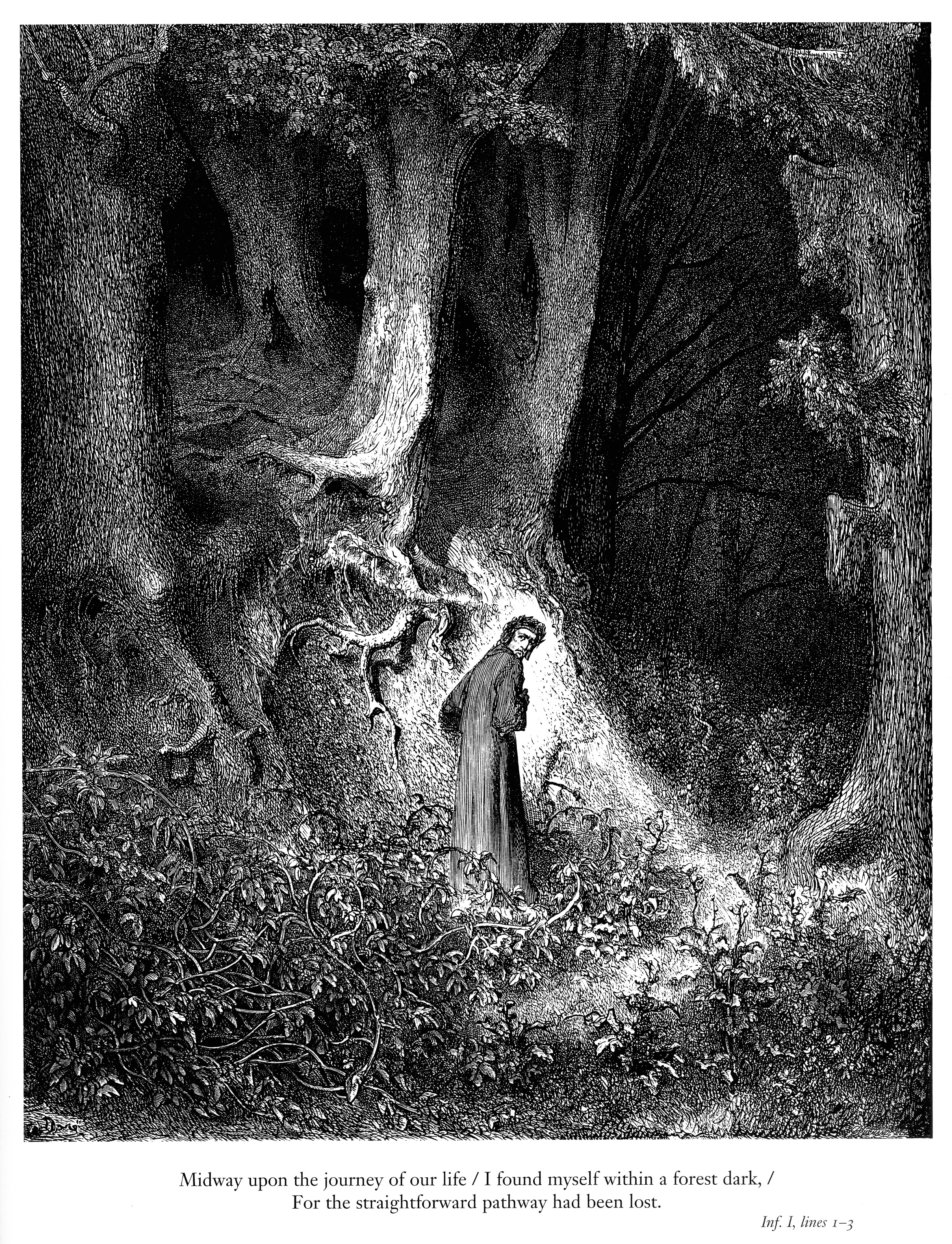

Canto I (Inferno) : The Forest Dark (Week I)

The soul must prove its courage and ability, it's inherent truth, as the body must prove its strength and skill in an athletic contest.

~ from Dante: Poet of the Secular World by Erich Auerbach

Welcome to Dante Read-Along!

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

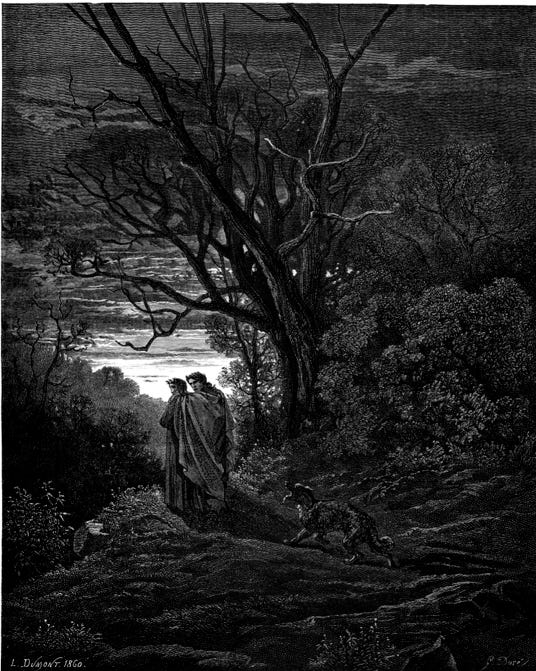

Welcome to Dante Read-Along, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this first Canto we meet him in the shadowed forest. You can find the main page of the read-long right here, reading schedule here, and the list of characters here (coming soon).

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, spiritual (philosophical) exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character and symbolism explanations.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️ :

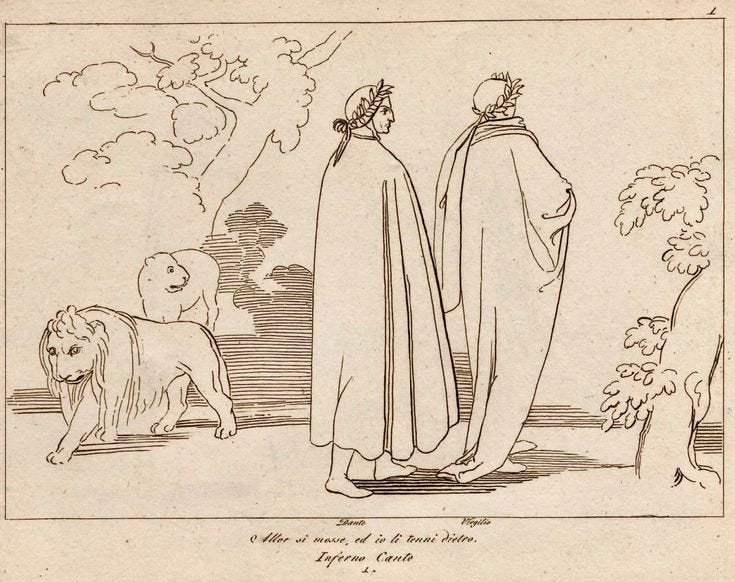

Dante is lost in the dark wood after straying from the right road - He tries to ascend a mountain but is held back by three beasts, the leopard, the lion and the she-wolf - He is approached by the shade of the poet Virgil, who tells him he cannot ascend by the short path of the mountain - Only the Greyhound can bring redemption from the she-wolf - Virgil offers to guide Dante away from the wandering path and through Hell and Purgatory - Thereafter one worthier than he will guide Dante into Paradise - They set off

Canto I: Summary 🌒

We open our journey meeting Dante as character and pilgrim, who is lost in a dense wood. His experience there, as he recounts it, is so visceral and profound that later, he could summon the feeling of it again. This fear, as we shall find, is not the fear of the body, but of the lost soul. He entered that wood as a sleepwalker, not even sure of how he arrived there, but upon entering it, knew he had “left the true path (1.12), the “path that does not stray”(1.3). Even though lost, he knew that there was a journey to follow that held a certain order and he longed to find the way.

Here, as he looked up to the top of the mountain, he saw the light of the sun bathing it, and the mountain became symbolic of the soul’s ascent to divine understanding and fulfillment. His fear was quieted by the sight of the sun, which to him was the fourth planet in medieval, Ptolemaic cosmology, and represented the power of the most high God. Here, Dante gives us his first epic simile (1.22-28), moments of sublime description fraught with emotion and feeling.

Dante took stock of where he stood, on the edge of the wood, in the valley at the base of the mountain before the ascent on high, and began to climb. He began the ascent with no help, on his own initiative, seeing the beauty of the sun that was above him. Yet he was immediately held back from that ascent by the appearance of a beast, a leopard who blocked his path. No sooner did he turn aside than a hungry lion also made its appearance, and next a ravenous she-wolf. Here, all hope was lost; when confronted by these representations of his own error, Dante “abandoned hope” (1.53) of climbing the mountain and reaching the safety of the illumined sun, or God. Here we come across another epic simile (1.55-60) expounding upon his despair, tallying his loss.

In Dante’s retreat away from the mountain and the beasts, he beheld an image, and not knowing who or what it was, called out for help. Throughout his journey, as we will see, Dante is not afraid to ask for help or sympathy when he feels he cannot do what is in front of him. This very moment is the moment of deepest crisis, caught between worlds of the dark wood and the inaccessible mountain; unable to go forward, Dante calls out for help, unaware of whom it is he calls to. The answer he receives is at first cryptic, with the speaker describing himself without naming himself. He identifies himself as a poet who was born sub Julio or under Julius Caesar, and lived in Rome under Caesar’s adopted son, the Emperor Augustus. In his poetry he praised the “son of Anchises who had come from Troy” (1.74-75), being Aeneas, the hero of the epic Latin poem the Aeneid, the poem detailing the origins of Rome, praising the city and all that it stood for at its height. This shade, the soul without a body, this hidden figure, asks Dante why he is going back to the dark wood, “to wretchedness” (1.76), as Dante attempts to flee the beasts.

Dante is already so familiar with the speaker through his work that he recognizes him immediately: Virgil.

The significance of Virgil to Dante is supreme, and Dante first expresses this by praising him; “my long study and the intense love / that made me search your volume serve me now” (1.83-84). Dante has studied the poet so deeply that his wisdom seems to have become embodied, and for Dante that embodiment becomes a reality. For Virgil was held, throughout the ages, as simply “the poet”; so well known was his verse. He was studied in a way that we can hardly conceive of studying a single author now.

As Dante praises his newfound guide, Virgil tells him that he must take another way than that which he was just attempting. The beasts - our passions - are impossible to tackle alone, or by shortcut. The nature of craving that is the hallmark of avarice - the she-wolf - is never satisfied; in fact, each time the beast feeds, it becomes even hungrier and craves even more. Only the Greyhound can redeem Italy from the political and moral crisis that it is in and bring it into order, the order from which Camilla, Nisus, Turnus and Euryalus - characters from Virgil’s Aeneid - died.

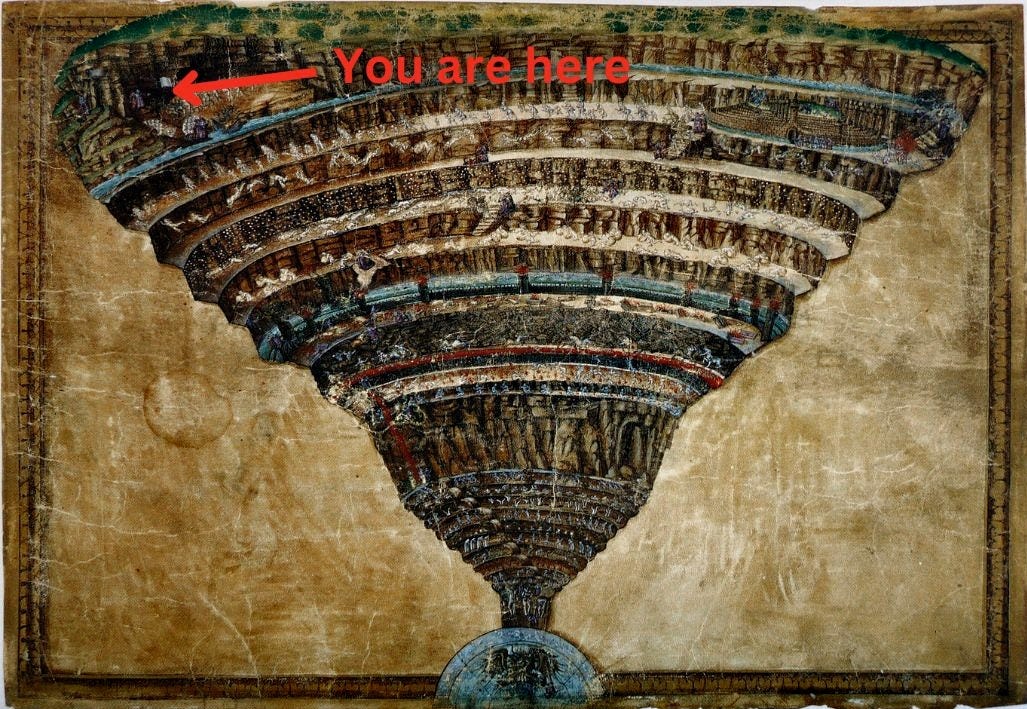

He offers to guide Dante, taking him away from this wandering path through the ordered architecture of Hell (Inferno) and Purgatory (Purgatorio).

Beatrice - she who awakened Dante to Love - is foreshadowed here as one who will guide Dante after Virgil, who can only take him so far, being a virtuous pagan who is unable to enter Paradise. Dante agrees to be led through these realms, and they depart.

💭 Philosophical Exercises: What to do when even ‘The Sun to you is dark’?

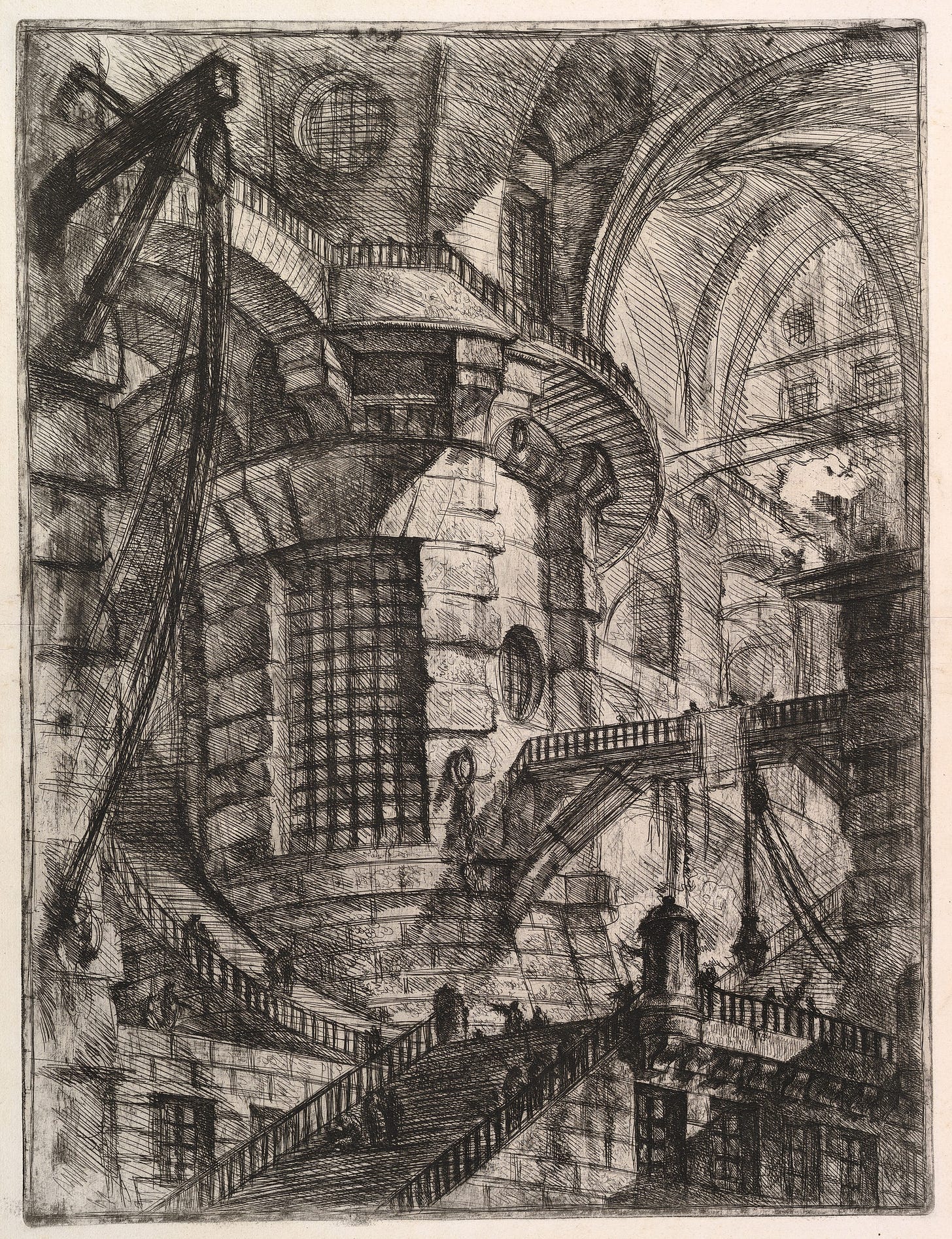

The first Canto of The Divine Comedy often reminds me of this drawing by the 18th century Italian architect Giovanni Battista Piranesi. This one depicts a prison and if you pay a close attention, it’s a prison with false paths, stairs that lead nowhere, bridges with no doors on either sides. This is our mind in chaos, intellect trapped in the labyrinth of one’s thought, a soul with low moral reasoning, a will with no strength.

There were many minds who remained free in physical prisons, but none that escaped confines of a mental one.

This where Dante find himself. This is the place from which he tries to escape.

I. If Eden was a Garden, then Hell surely must be a Forest.

The Divine Comedy is far more than fiction; it’s a profound exploration of the soul, the psyche, and the very essence of being—whatever you choose to call it.

‘The poet, when he painted hell, was painting his life…’ wrote Victor Hugo in his poem After Reading Dante. My reader might have noticed the curious play of words by Dante right in the first lines of the poem:

When I had journeyed half of our life’s way,

I found myself within a shadowed forest,

In the original Italian ‘di nostra vita’ and then ‘mi ritrovai’ - a beautiful way to balance individual (or, I) with universal (our). To paraphrase Hugo: ‘By painting hell, the poet was painting his life…, but also lives of all of us’.

Dante awakens in the dark forest—not as a dream, not as a hallucination, but as if he is physically there, gripped by fear. The dark wood that he finds himself in does not symbolise sin, but a life lived in a condition of sin. If Eden was a garden, then Hell must surely be a forest. Dante’s sinful life - as described by Hollander - is as though he lived in the ruins of the Garden of Eden.

It’s worth noting that Dante structured his Inferno and Purgatorio on a foundation of Aristotelian and Ciceronian ethics, intertwined with Christian concepts such as heresy. Thus, when we speak of “sin” in this poem, we refer to it as much in a philosophical sense as in a theological one.

If I follow in the footsteps of my intellectual hero Pierre Hadot, who saw great literature as a source of spiritual and philosophical exercises, the first lesson from this Canto is clear: we should be aware of our mental state. Awareness that our decisions and free will determine where we find ourselves is central to the Aristotelian idea that our choices shape our destiny. As the proverb says, “Demons become less scary when they are stared in the face.” Refusing to confront our demons (faults, weaknesses) and take responsibility for our actions ultimately lead us into the dark wood.

II. Can Dante Be Your Virgil? (Your Guide Out of Hell?)

Dante awakens from his “sleep,” realising that it was the state of his character that led him into the darkness. Dante cannot recall how he ended up here since he was so ‘full of sleep’ meaning - the loss of intellectual, moral, and spiritual awareness.

To escape and find bliss, he must transform himself. Recognising and acknowledging this is a significant first step, but the act of change is far more challenging. He is ‘aware’ now of his weaknesses and faults, but how did he slip into this state of ‘sleep’? What dulled his character?

We fall into a spiritual slumber if we lose our sense of moral reasoning. When Dante encounters the three beasts: lust (leopard), pride (lion) and greed (she-wolf) - he backs down and stops his progress towards the planet (sun), but why?

He is doing what any of us would do: becoming aware of his peril. He sees the Sun, the guiding light that leads all to the right path, but when confronted by the beasts, he retreats into despair—a despair so profound that even ‘the Sun is silent.’ He cannot overcome these beasts, because he is morally and spiritually weak.

It is impossible to discuss this without mentioning Boethius, the author of the remarkable The Consolation of Philosophy1. Dante was profoundly influenced by the wisdom of this philosopher. Boethius wrote his masterpiece during his final days in prison, where the figure of Lady Philosophy appeared to him, offering solace and guidance through her wisdom.

The parallels between Lady Philosophy’s appearance as Boethius’s guide and Virgil’s role as Dante’s guide are striking and deeply significant. They both remind our characters of wisdom they had forgotten.

“It is another path that you must take” says Virgil, Dante’s guide, who appears to Dante as ‘a shade’. Many commentators believe that Virgil represents our faculty of reason and throughout this journey Virgil instructs, protects, explains, scolds and inspires his terrified companion.

Dante once again places meaning in plain sight, waiting for those willing to see it. As I mentioned earlier, Virgil first appears to him as “a shade.” However, as he draws closer to Dante, his form becomes more distinct, and by the end of our journey, he will feel more alive to us than anyone we know in the flesh.

Only with solid wise reason we can rebuild our life again.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Themes 🖼️ :

Fear ( ‘Paura’ Italian)

The word ‘fear’ is mentioned five times in the first canto, more than in any other later Canto in The Divine Comedy. Fear, as I mentioned in my previous piece, acts as a catalyst for spiritual and mental transformation.

The journey of the soul.

From sin to salvation. From ignorance to truth. Dante was influenced by Neoplatonic concept of our soul being able to ascend to higher states. I explored this in my piece on How to Sculpt Your Own Soul.

is particularly interested in these ideas and will be a better source if you’d love to delve deeper.Spiritual work

Of course, ‘spiritual work’ is closely linked to the earlier theme of ‘the journey of the soul,’ emphasising that there are no shortcuts in spiritual growth. Dante see the Sun, the celestial body that guides all toward the right path, yet he cannot reach it without a guide, divine grace (more on this in the next canto), and a descend into Inferno.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom)

This week’s quote coincided with the Epic Simile section below, where Dante compares his escape from the forest to someone who escapes from sea to the shore.

Not to repeat the same one twice in a single post, allow me, to use another quote here, not lesser in its meaning and beauty:

For your sake, I think it wise

you follow me: I will be your guide,

leading you, from here, through an eternal place

where you shall hear despairing cries

and see those ancient souls

as they bewailed their second death.2

Dante, a profound genius of the human psyche, reveals that there are ways of living where death itself might seem like a form of redemption. Those condemned to eternal punishment in Inferno long for death as an escape from their torment.

This is also why, when Dante exits the forest he turns back (see simile quoted below) he says that he left a place ‘that never has let any man survive’. Sometimes, only a miracle can lead us to escape from the confines of our mental prisons.

Terms:

Epic Simile:

Dante uses the technique of the epic simile - sometimes also called the Homeric simile - in each Canto as a signature of his poetic brilliance. In fact, there are over 400 different similes in The Divine Comedy. Think of Dante holding an idea, and rather than just telling us what the idea is in exact language, he begins walking around the idea in a circle, describing it, drawing it out, feeling it. This is the epic simile. We find examples in every Canto.

The first example he gives us is in 1.22-28:

“And just as he who, with exhausted breath,

Having escaped from sea to shore, turns back

To watch the dangerous waters he has quit,

So did my spirit, still a fugitive,

Turn back to look intently at the pass

That never has let any man survive”

Characters:

Dante:

Dante Alighieri, the Florentine poet who lived from 1265-1321, is the poet as well as the character of the pilgrim. Dante was not only a poet, but a philosopher, a theologian, and a politician. His poetry was celebrated during his lifetime, although he lived in exile from his native Florence.

The Three Beasts: Dante is confronted with his own inner disorder and error, which is here represented by three predatory animals: the leopard, the lion and the wolf.3 Their descriptions hearken back to biblical references: “Wherefore a lion out of the forest shall slay them, and a wolf of the evenings shall spoil them, a leopard shall watch over their cities: every one that goeth out thence shall be torn in pieces: because their transgressions are many.”4 There has been much debate over the meaning of these three beasts, but most scholars agree on the interpretation of the leopard symbolizing lechery or lust, the lion as one of pride or violence, and the wolf as a symbol of avarice and greed. Each level of Hell, then, is ruled by one of these themes.

Virgil: - Poet and Guide, Publius Vergilius Maro (70BC -19BC), better known simply as Virgil, represents Reason as the means for guiding Dante, at the behest of Beatrice, through Hell and Purgatory. He studied and wrote epic poetry in the reign of Augustus Caesar under his patron Maecenas, alongside other poets of his day, including Horace. Themes from his epic poem the Aeneid are found frequently in the Inferno. His major works include the Georgics, the Eclogues, and the Aeneid.

Camilla: In the Aeneid, Camilla is the daughter of King Metabus of the Volsci, who ultimately fights with the Trojans on the side of Turnus. She is killed during battle in book 11 of the Aeneid, her last words being “ Go, quickly, carry my last commands to Turnus: / Take over the fighting, free the town from Trojans! / Now farewell.”5

Nisus and Euryalus: The friends who sneak into the enemy camp under the cover of night to wreak havoc and slaughter the enemy in their sleep in book 9 of the Aeneid, only to be found out by the glint of moonlight on a helmet. Both were killed by the Rutulians.

Turnus: In Virgil’s Aeneid, Prince of the Rutulians, rival of Aeneas and the Trojans, both on the battlefield and for the hand of the princess of Latinum, Lavinia. The final scene in the Aeneid is the death of Turnus at the hand of Aeneas, whose “life breath fled with a groan of outrage / down to the shades below.”6

Next Circle (Canto II) ⭕️:

We learn how to conquer cowardice. Dante is afraid to begin this journey. Virgil reminds him of his (our) divine origins.

A wonderful work of philosophy that will transform your perspective on life completely. Maybe after Dante, we can do a short (since the book itself is only 100+ pages long) read-along of Boethius! Let me know if you would be interested!

I used Robert and Jean Hollander’s translation in this passage, instead of Mandelbaum.

Charles Williams, The Figure of Beatrice 109

King James Version, Jeremiah 5:6

Aeneid 11.963-969

Aeneid 12.1112-1113

I'd definitely be interested in a subsequent read-along of Boethius.

The French philosopher Paul Virilio said “When you invent the ship, you invent the shipwreck.” I’ve thought in Dante’s case he did just the opposite — he created the “shipwreck” (the pilgrim’s plight) in order to invent the “ship” (the journey). He did compare his anxious, troubled pilgrim, as you note, to a swimmer “…with exhausted breath, having escaped from sea to shore…” The pilgrim’s “dark night of the soul” certainly seems to echo Psalm 88 (and your theme of Fear, perhaps).

You point out in the character description that Virgil was dispatched by Beatrice; it might be worth noting the key lineage of this directed intercession — tasked from the Blessed Virgin Mary to Lucia to Beatrice (who of course assumes the task of guiding and teaching after Virgil, and is then succeeded by St. Bernard of Clairvaux).

You mention three themes; others also noted his aspiration for (what I would call) “right-ordered” politics, and, of course, finding Beatrice (the guide of and to his soul). Any woman that earns this flattery (“Behold, a deity stronger than I; who coming, shall rule over me”) is bound to feature prominently in his quest!

I’m curious if you or Lisa have an opinion on the enigmatic “greyhound”? Is it simply symbolizing salvation? Is it meant to infer Christ? Cangrande della Scala? The Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII?