Ripley & Dante: I Wear the Skin of Those I’ve Robbed

(Inferno, Canto XXIV): Thieves, Vanni Fucci, and the Masks We Can’t Take Off

I wear the skin of those I’ve robbed, / A mask that shifts with every breath I’ve sobbed.

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

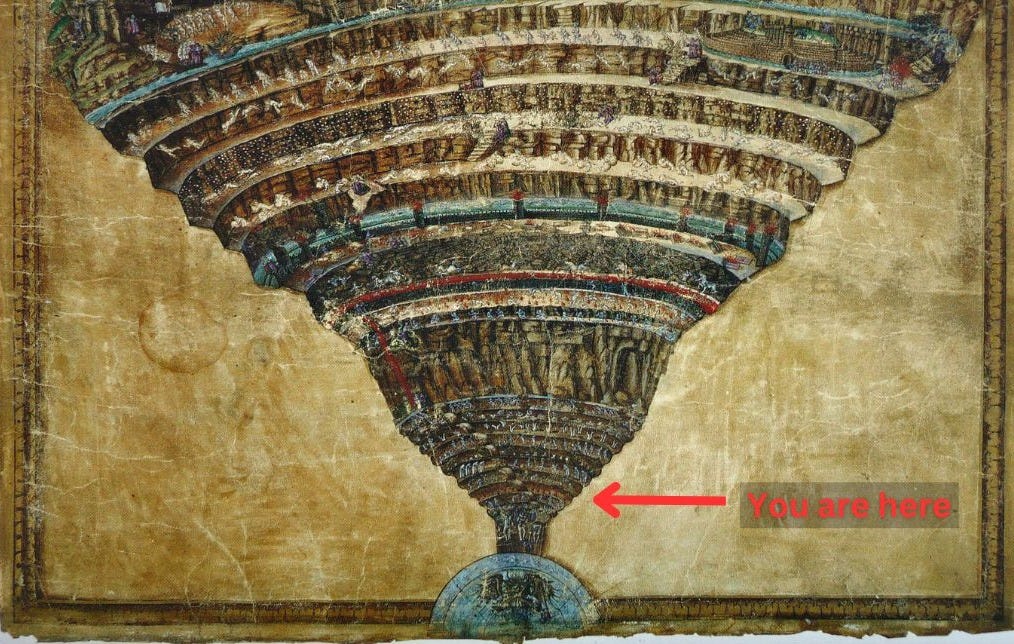

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Twenty-Fourth Canto we enter the seventh bolgia of the Eighth Circle and find the Thieves. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Eighth Circle, Seventh bolgia - Dante and Virgil climb up the rocky bank out of the trench of the Hypocrites - No time to rest - The Seventh bolgia filled with serpents - The Thieves, bitten, fall to ashes and reform - Vanni Fucci - A prophecy of Florence.

Canto XXIV: Summary

The wave and retreat of Virgil’s anger stemming from the lie of the demons, the emotions embodied in the imagery of seasons and snowfall, expectations and fulfillment, opens the Canto with an extended simile; Dante feels the subtle changes in Virgil just as Virgil had read Dante’s emotions when they were of one mind in escaping the demons of the sixth bolgia.1

So did my master fill me with dismay

when I saw how his brow was deeply troubled,

yet then the plaster soothed the sore as quickly:

XXIV.16-18

They reached the base of the shattered bridge that they had to climb, and Virgil, having restored his “sweet manner”2 after his justified anger, examines the way that they’ll ascend. Virgil again lifts Dante up as he had for their descent into the sixth bolgia, and guides him in climbing together up the embankment. The Hypocrites that they have just left would have been no match for this climb in their heavy, lead lined cloaks.

The angle of their climb out was lower than that of the slide down in the sixth bolgia because of the funnel shape of the Eighth Circle and their proximity to the smaller center; therefore this climb was a little more forgiving than it could have been, though still exhausting. Reaching the top, Dante in his weariness sat to rest, but Virgil calls for continuing their task and encourages him with a powerful speech to awaken his strength and fortitude.

Therefore, get up; defeat your breathlessness

with spirit that can win all battles if

the body’s heaviness does not deter it.

A longer ladder still is to be climbed;

it’s not enough to have left them behind;

if you have understood, now profit from it.

XXIV.52-57

While this “longer ladder” refers to Purgatory, how much more can it mean the daily struggle of life?

Even when the whole descent into Hell is accomplished, there remains the steep ascent to Purgatory. To renounce sin is not all: the active work of purgation remains to be done before [Dante] can be reunited with Beatrice.3

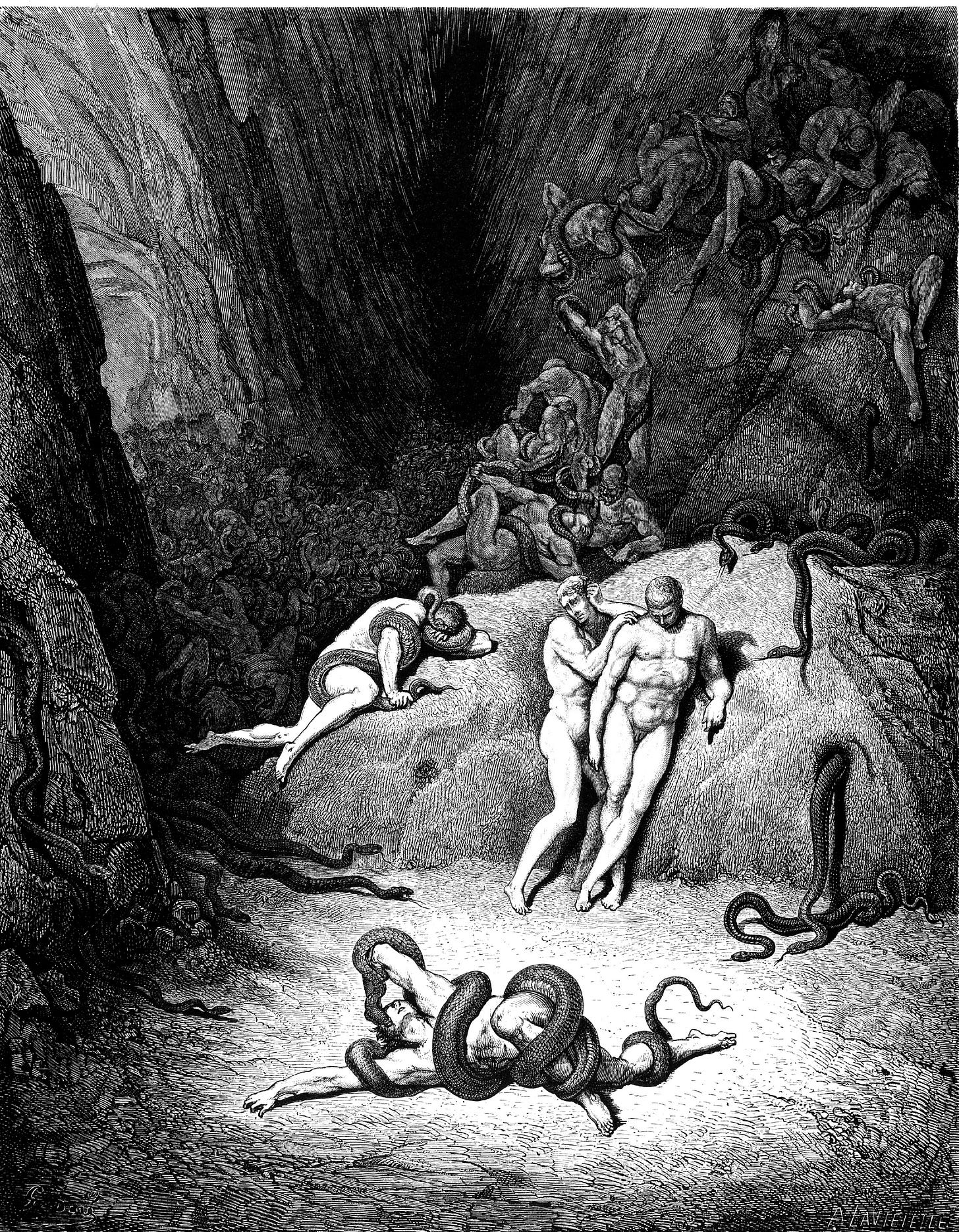

Invigorated by Virgil’s speech, Dante stands and is ready to go on. They crossed the steep and narrow bridge over the seventh bolgia, and from below Dante heard a voice, indistinct, one “not suited to form words” (66). In order to see and hear better, they finish crossing the bridge and stand on the lower, further edge of the seventh bolgia.

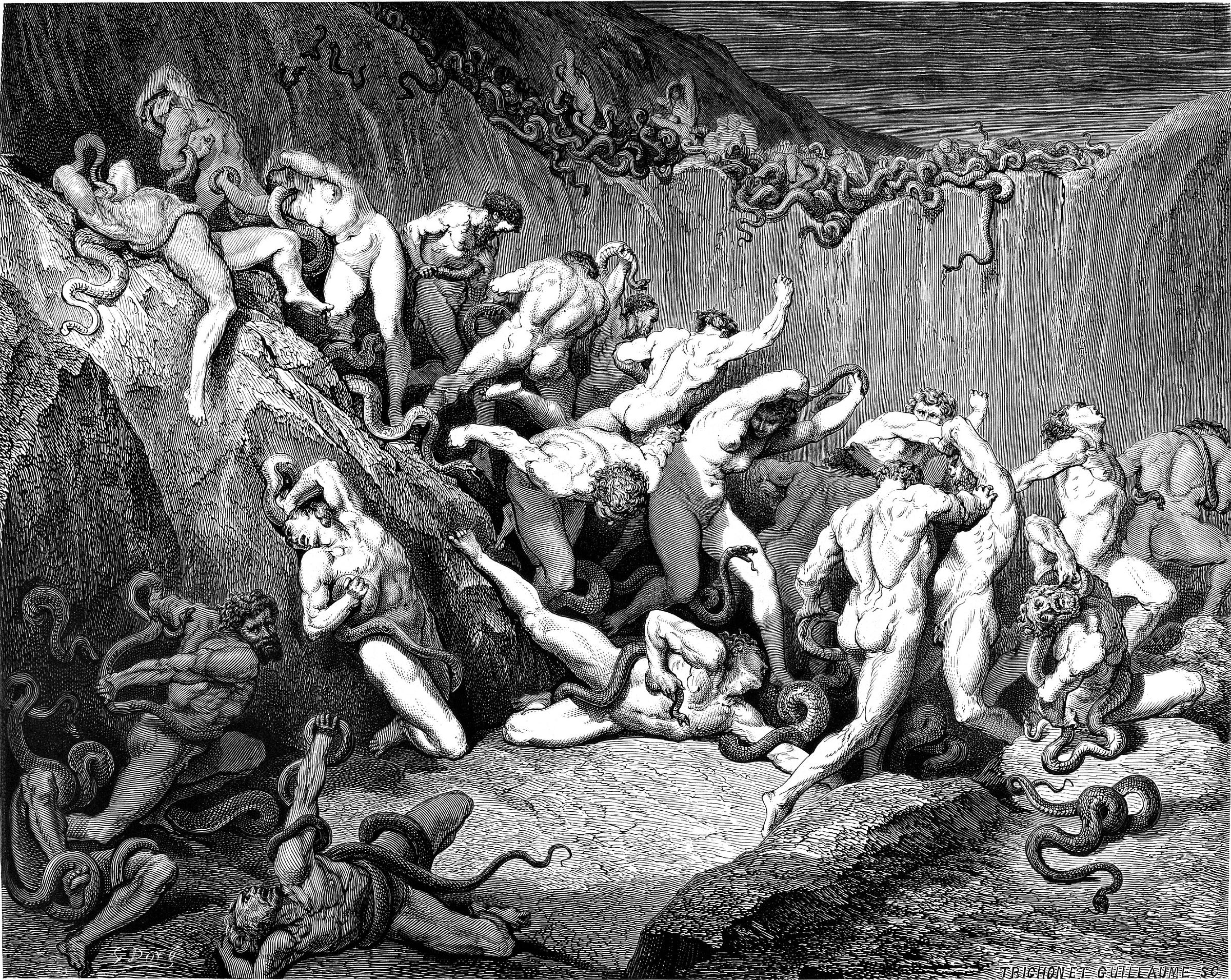

When they were close enough to see, the blood-chilling sight that met them was of a trench filled with serpents; more serpents than could be found in all of Northern Africa. Lucan’s entry on the names and characteristics of the snakes of Libya, from which Dante drew, runs thus:

But the mighty Haemorrhois which will not let

Its victims’ blood stand still unfolds its scaly coils,

And Chersydros, born to live in the fields of Syrtes,

Land and sea, and Chelydros, drawn along with smoking track,

And Cenchris, which will always glide along a direct path:

It is tinted on its dappled belly with more marks

Than Theban serpentine adorned with tiny flecks.

Lucan Pharsalia IX.708-714

Within this bolgia, among these serpents, run the sinners, their plight all the more pitiable because of their nakedness; there was no refuge in which to hide, no magic stones to bring them invisibility. As yet unnamed, these symbols of deceit entwine with the nature of the sinners of this bolgia: the Thieves.

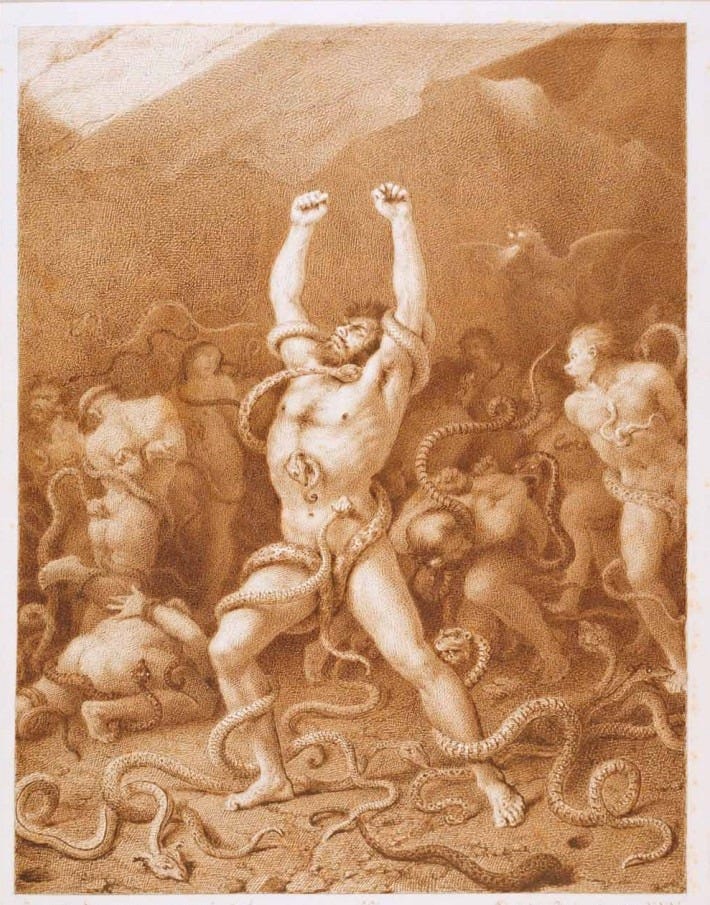

The Thieves' hands were tied with serpents, which coiled around them. Dante saw one running sinner be bitten on the neck by a serpent, and immediately crumble to ash. Those ashes bound themselves together again to reform back into the sinner. Dante compares this to the phoenix, as found in Ovid:

But one alone,

A bird, renews and re-begets itself—

The Phoenix of Assyria, which feeds

Not upon seeds or verdure but the oils

Of balsam and the tears of frankincense.

This bird, when five long centuries of life

Have passed, with claws and beak unsullied, builds

A nest high on a lofty swaying palm;

And lines the nest with cassia and spikenard

And golden myrrh and shreds of cinnamon,

And settles there at ease and, so embowered

In spicy perfumes, ends his life's long span.

Then from his father's body is reborn

A little Phoenix, so they say, to live

The same long years.

Ovid, Metamorphoses XV.394-401

The sinner gazed uncertainly about him as he regained his senses after this dissolution, until Virgil asked him who he was. It is here that the sin of the Thieves is finally named; the speaker is Vanni Fucci of Tuscany.

Vanni Fucci broke into and plundered the treasure of San Jacopo in the church of San Zeno at Pistonia, for which crime a namesake of his, with whom he had deposited the booty, was hanged, Vanni having revealed his name.4

Vanni assumes that Dante is happy to see him there - in Hell - even as he was ashamed at being recognized, as they were on the opposite sides of the Florentine political sides; Dante was a White Guelf and Vanni was a Black Guelf. He was not with the Violent in the river Phlegethon as Dante would have guessed, based on what he knew of him, but here with the Thieves, the sin calling out his true nature. Fucci was known as a beast, it was even a nickname, and is in this realm because of theft of the sacristy, or sacred items, from the church.

Vanni gives his prophecy, predicting the downfall of Dante’s party and their exile from Florence for their role in casting out Vanni’s Black Guelph party. Using meteorological imagery, Vanni predicts:

From Val di Magra, Mars will draw a vapor

which turbid clouds will try to wrap; the clash

between them will be fierce, impetuous,

a tempest, fought upon Campo Piceno,

until that vapor, vigorous, shall crack

the mist, and every White be struck by it.

XXIV.145-150

The prophecy brings an abrupt end to Canto XXIV.

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

‘Not caught - Not a thief’

(Не пойман - не вор)

~ Russian proverb

My father, like a devoted gardener tending a delicate flower—watering it at just the right time and watching it grow—is the one to whom I owe my passion for Dante’s The Divine Comedy. For years, especially during my teenage years, he nourished me - like that devoted gardener who waters his flower - with passages from Dante—always at the moments I needed them most. One of the verses he often recited to me came from this very canto we are exploring now:

The breath within my lungs was so exhausted

from climbing, I could not go on; in fact,

as soon as I had reached that stone, I sat.“Now you must cast aside your laziness,”

my master said, “for he who rests on down

or under covers cannot come to fame;and he who spends his life without renown

leaves such a vestige of himself on earth

as smoke bequeaths to air or foam to water.Therefore, get up; defeat your breathlessness

with spirit that can win all battles if

the body’s heaviness does not deter it.A longer ladder still is to be climbed;

it’s not enough to have left them behind;

if you have understood, now profit from it.(Mandelbaum, lines 43-47)

The visual description of life spent without renown being similar to ‘smoke bequeath[ed] to air or foam to water’ is unforgettable. In times of crisis, when my will begins to falter, I return to this wisdom from Dante. Since 2014, it has appeared on the first page of every Moleskine journal I’ve kept—a quiet reminder of strength when I need it most.

It was only recently that I found myself wondering: why does Virgil appeal to fame, and not—for instance—to the Divine Grace that awaits Dante at the end of his journey?

If we were to imagine Saint Thomas as guide here, we would expect his words to have been quite different.5 This—that Virgil ought to have directed Dante toward Divine Grace—is, I believe, a mistaken view. Since we all know someone—whether personally or from afar—who devotes their entire life to divine matters, forgetting that life must also be lived. Lived in accordance with divine harmony, yes, but lived nonetheless. Memento vivere—remember to live.

The fame that Virgil points to is not the same fleeting, vain renown pursued by Brunetto Latini, as we saw in Canto XV. Rather, it is a different kind of fame—one that grants immortality. It is the enduring memory of a life lived in harmony with virtue, the kind of glory that time does not erase. A fame should be intertwined with virtue, otherwise it is a hollow echo rather than a lasting legacy.6

I. The Talented Mr. Vanni

And—there!—a serpent sprang with force at one

who stood upon our shore, transfixing him

just where the neck and shoulders form a knot.No o or i has ever been transcribed

so quickly as that soul caught fire and burned

and, as he fell, completely turned to ashes;and when he lay, undone, upon the ground,

the dust of him collected by itself

and instantly returned to what it was:just so, it is asserted by great sages,

that, when it reaches its five—hundredth year,

the phoenix dies and then is born again;

Just when you think the punishments in Inferno could not grow more dreadful, you descend a level deeper and discover—yes, they can. The eternal, grotesque metamorphoses that the thieves endure left me chilled, afraid even to imagine the torment of their ever-shifting, unstable forms.

There is a reason why the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung believed that the structure of our psyche closely resembles Dante’s The Divine Comedy. Dante shows us that ‘a thief’ is not simply a person who steals from your pocket when you are looking the other way, but a whole shifting identity, something that was perfectly displayed by Steven Zaillian’s adaptation of Ripley by Patricia Highsmith.

“La luce. Sempre la luce.” (Light. Always the light.)

(Don’t worry, I am not going to mention any spoilers)

Thomas Ripley is a con artist and a consummate thief. He doesn’t just steal possessions—he steals entire lives. Identities become costumes he puts on and sheds as needed, leaving behind no stable self. When the threat of exposure arises, he simply vanishes behind a new mask. And the deeper you follow him, the clearer it becomes: there is no real face beneath the disguise. Ripley is not a man wearing many masks—he is the mask, ever-shifting, elusive, and unknowable.

Zaillian masterfully weaves the fictional enigma of Tom Ripley with the real-life shadow of another elusive genius—Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio.

Caravaggio, the maestro of chiaroscuro, used light and darkness not only as a technique but as a language—shrouding some elements in shadow, casting a piercing glow on others, guiding the viewer’s eye with deliberate manipulation. Ripley, the thief, employs the same method with truth. He buries the inconsistencies of his lies in darkness, while highlighting just enough illusion to convince, to charm, to pass.

Like the souls in Inferno, Ripley is plagued—bitten not by serpents but by the relentless anxiety of exposure. And like them, he is forced to undergo endless metamorphosis. He must destroy himself again and again, shedding each forged identity in fire, only to rise from the ashes like a phoenix, reborn in another borrowed life.

II. Final Thoughts

Vanni does not repent for his sins, he has no remorse. He runs away from Dante and Virgil not because he is horrified of what he has done, but because he was exposed. The parallels between Zaillian’s interpretation of Ripley and Dante’s description of thieves, and Vanni in particular, in Inferno are striking.

The character of Tom Ripley, as Vanni, never expresses any regret for what he has done, he is only ashamed of being caught, for needing to vanish like a phoenix once again.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Ruined Path as a Way Forward

It is easy to miss that Dante and Virgil climb over the scree that was the result of the earthquake that shook the universe after the Christ’s Crucifixion.

And he examined carefully the ruin;

then having picked the way we would ascend,

he opened up his arms and thrust me forward.~ lines 22-24

The path that was once intact was ruined—here we also must remind ourselves of Empedocles’s philosophy from Canto XI—and it is curious to see that after meeting hypocrites, and particularly Caiaphas, who was responsible for Christ’s crucifixion, we have to climb through the scree that was the result of Caiaphas’s hypocrisy. It is mind-blowing to see that there is literally not a single line in this poem, neither a single scene nor place, which is superfluous. Everything in Dante’s universe is intertwined. What also struck me as phenomenal is that Dante’s will falters here, since it is as if he is crossing another realm by conquering these boulders.

Sometimes even the intelligent thinkers can say stupid things.

I admire John Ruskin deeply. Many of his ideas have shaped my thinking in ways that are hard to describe. I even recorded a podcast episode with his biographer, Suzanne Fagence Cooper. Perhaps this is why I felt particularly disappointed to discover that, in Modern Painters, Ruskin wrote about this part of the Inferno: “Dante was a notably bad climber.”

I checked carefully—there is no hidden meaning in his remark. He simply took the scene at face value, stripped of its symbolic and profound layers. How a man capable of such penetrating insights into art could be so blind to the depth of this passage remains a mystery to me.

Nine Prophecies

Not knowing how else to wound Dante for catching him in the Inferno, Vanni delivers the ninth and final prophecy of the Inferno.

If you have understood, now profit from it.

I would not have been able to forgive myself if I didn’t remind both myself and you, my reader, of a short phrase spoken by Virgil: “If you have understood, now profit from it.”

I remind myself often that this read-along is not just about understanding Dante’s wisdom more deeply—it is about profiting from that understanding. Comprehension is only the first step; transformation must follow.

You could read a hundred books a year and even grasp them fully, but if you do not profit from them, all your efforts may be in vain.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

The breath within my lungs was so exhausted

from climbing, I could not go on; in fact,

as soon as I had reached that stone, I sat.“Now you must cast aside your laziness,”

my master said, “for he who rests on down

or under covers cannot come to fame;and he who spends his life without renown

leaves such a vestige of himself on earth

as smoke bequeaths to air or foam to water.Therefore, get up; defeat your breathlessness

with spirit that can win all battles if

the body’s heaviness does not deter it.A longer ladder still is to be climbed;

it’s not enough to have left them behind;

if you have understood, now profit from it.

See Inf. XXIII.25-30

See Inf. I.61-78

Sayers Hell 225

Singleton, Commentary on the Inferno 420

Hollander, Commentary to Inferno XXIV, page 459

Each essay introducing us to a Canto has been a multifaceted gem, yet this one exists on an entirely different plane. For me, the most moving and enthralling passage in the essay is this: “My father, like a devoted gardener tending a delicate flower—watering it at just the right time and watching it grow—is the one to whom I owe my passion for Dante’s The Divine Comedy. For years, especially during my teenage years, he nourished me - like that devoted gardener who waters his flower - with passages from Dante—always at the moments I needed them most.” Vashik, by this alone, you are uniquely suited to be our guide on this journey. Thank you.

I got stuck around Canto IV, because I wanted to read and take notes and got overwhelmed. I have slowly been reading, and not taking notes, so I can catch up. These essays are so thought provoking. I'm a simple reader with no background in the classics or humanities. You mention being disappointed with what Ruskin did not see. We're each such unique people, we can't all see everything. Ruskin gifted us with many insights, and now so do you. Each expresses your unique vision and insight. Thank you!