When Words Wound Deeper Than Blades

(Inferno, Canto XXVIII): Scandal and Schism, Mohammed, Curio and sowers of discord

But all was false and hollow; though his tongue

Dropp'd manna, and could make the worse appear

The better reason, to perplex and dash

Maturest counsels.

~ from John Milton’s Paradise Lost

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

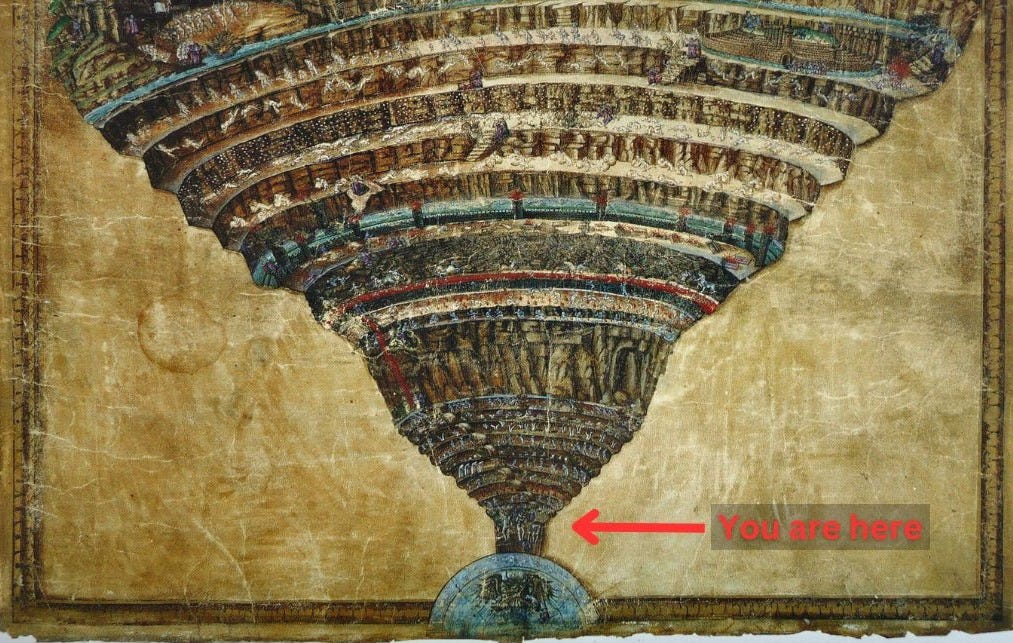

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Twenty-Eighth Canto we examine the ninth bolgia of the Eighth Circle and encounter the Sowers of Discord. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Eighth Circle, ninth bolgia - Sowers of Scandal and Schism - Sinners wounded by devils with swords - Mohammad and Ali - Pier da Medicina - Curio - Mosca de Lamberti - Bertan de Born holding his head like a lantern.

Canto XXVIII Summary:

Schism takes its name from being a scission of minds, and scission is opposed to unity. Wheretofore the sin of schism is one that is directly and essentially opposed to unity…Hence the sin of schism is, properly speaking, a special sin, for the reason that the schismatic intends to sever himself from that unity which is the effect of charity.1

The ninth bolgia of the Eighth Circle presented a dark and disturbing sight; so intense, so epic, that describing it was a nearly impossible task.

Each tongue that tried would certainly fall short

because the shallowness of both our speech

and intellect cannot contain so much.

XXVIII.4-6

We have traveled so deep into the recesses of hell that the human mind can barely comprehend it. The Sybil expressed a similar sentiment to Aeneas during their journey to the Underworld:

Had I a hundred tongues and a hundred mouths and an iron

voice, I would still fall short of the power I would need to encompass

every species of crime or name all those judgements inflicted.

Aeneid VI.625-627

To express the vastness of the mutilated bodies before him in the ninth trench, Dante recounts battle after battle, having us visualize all of those dead and wounded on display; yet even this picture does not show the full extent of the blood and gore he sees before him;

That would not match the hideousness

of the ninth abyss.

XXVIII.20-21

Dante tells of battles, of so many battles. He tells of the bloodshed in the region of Apulia in southern Italy, called Puglia in his day; he tells of the defeat of the Romans by Hannibal’s army in the battle of Canae in the second Punic War, in which so many were killed that three bushels of rings taken from their bodies were presented to the senate at Carthage to prove the extent of the victory.

At that point, to prove how successful the campaign had been, Mago ordered gold rings to be poured out at the entrance to the senate house. The mound they formed was so great that, according to some sources, they amounted to more than three measures (though the story that has prevailed—and this is closer to the truth—is that it was no more than one measure). Mago then added a commentary to make the defeat look even greater: only knights wore this status symbol, he said, and of knights only the most distinguished.2

There is yet more; he tells of the bodies of the Greeks and Saracens who fought against and lost to Robert Guiscard — whom Dante places in the heaven of Mars in Paradiso XVIII.48 — he who fought as a Christian warrior for the faith, his goal to keep the Church strong against their enemies.

He tells of the clash at Ceperan, in which King Manfred was betrayed by the Count of Caserta, who allowed the troops of King Charles of Anjou to approach without attack, leading to Manfred’s defeat; and finally, the battle of Tagliacozzo, where Charles of Anjou again suffered a loss against Manfred, this time led by his nephew.

If the slain and wounded of all of these battles were brought together, they would be as nothing to the gory imagery Dante is witnessing now in the bolgia below.

And now they meet the first sinner in this realm, one who is split down the center from his chin to his anus; not only is his flesh split down the front, but his entrails and organs are hanging out, swaying between his legs. Dante could not help but stare as the sinner cried out and violently opened his wound even further, as if daring Dante to look more closely.

Here Dante places Mohammed, the founder of Islam — close behind him is Ali, his nephew, first follower, and son in law. Ali is split from his chin up to the crown of his head, complementing the wound of Mohammed.

There was a belief current in the Middle Ages that Mohammed was an apostate Christian, perhaps even a cardinal, and it may have been for this reason that Dante placed him in this ninth bolgia along with other great sowers of religious dissent. Or…the poet may have placed Mohammed here because he considered the founding of Islam a divisive factor in religious unity.3

The question of Ali’s succession of Mohammed after his death created yet another schism, this one within Islam itself, the division into two sects, the Sunni and Shiites.

Here is the sin of this bolgia first named: the sowers of dissension. The punishment of the gaping and bloody wounds are inflicted by devils with swords, and as the sinners make their circular way around the trench and back to the starting point, their wounds heal, only to be attacked again by the devils.

And all the others here whom you can see

were, when alive, the sowers of dissension

and scandal, and for this they now are split.

XXVIII.34-36

Three types are shown: fomenters of religious schism, civil strife and family disunion. They appear in the Circle of Fraud because their sin is primarily of the intellect. They are the fanatics of party, seeing the world in a false perspective, and ready to rip up the whole fabric of society to gratify a sectional egotism.4

Mohammed, having described himself and the bolgia, asks who they are, thinking they are shades trying to avoid punishment by standing above on the bridge. Virgil answers :

“Death has not reached him yet,” my master answered,

“nor is it guilt that summons him to torment;

but that he may gain full experience.

I, who am dead, must guide him here below,

to circle after circle, throughout Hell:

this is as true as that I speak to you.”

XXVIII.46-51

This got the attention of the other shades, and many stopped to look at Dante. Mohammed gave Dante a message for Fra Dolcino before leaving him to continue circling. Dolcino, who was still living, would be wise to heed the advice if he wanted to avoid being in this bolgia upon his death:

“Then you, who will perhaps soon see the sun,

tell Fra Dolcino to provide himself

with food, if he has no desire to join me

here quickly, lest when snow besieges him

it bring the Novarese the victory

that otherwise they would not find too easy.”

XXVIII.55-60

Fra Dolcino, or Dolicino Tornielli, led the sect the Apostolic Brothers after the death of its founder, Gherardo Segarelli. They taught a return to a life of poverty and chastity, in accordance with the lives of the Apostles, and in opposition to the opulence of the Roman Church. They were considered heretics and lived in hiding for a time before succumbing to starvation, capture, and massacre. Fra Dolcino and his companion Margaret of Trent were burned alive in 1307.

The next sinner that Dante encounters is Pier da Medicina, whose throat is slit and whose nose is sliced off deeply. He also has a warning for some above, due to the special foresight of those in hell told in lines 76-90.5

Guido del Cassero and Angiolello di Carignano, two noblemen of Fano, of opposite parties, were invited by Malatestino, lord of Rimini (see Inf. XXVII.46), to a conference at La Cattolica on the Adriatic coast. On their way to the rendezvous (or perhaps as they were returning) they were surprised in their boat by Malatestino’s men, thrown overboard, and drowned off the promontory of Focara.6

Dante says that if Medicina wants him to do this, then first he has to show Dante who it is that so “detests the sight of Rimini” (93), looking back to Medicina’s mention of “one who’s here with me / would wish his sight had never seen” (86-87).

This turns out to be Curio - now mute, with his tongue cut out - who acted as a catalyst for the Roman Civil War due to the advice he gave Caesar about crossing the Rubicon river, located in Rimini.

While the other side in panic has not fortified its strength, end delay! Procrastination always harms the men prepared for action.7

The next sinner, handless, with bloody stumps waving before him, is Mosca de Lamberti, the one responsible for the split in Florentine politics that created the Guelf and the Ghibelline factions; Dante adds a verbal wound to his wounds of punishment on noting that his words had brought so much death and destruction to his own people.

The great Guelf-Ghibelline feud in Florence flared up over a family quarrel. Buondelmonte dei Buondelmonte, who was betrothed to a girl of the Amadei, jilted her for one of the Donati. When her kinsfolk were debating how best to avenge the slight, Mosca dei Lamberti said: “What’s done is ended.” Buondelmonte was accordingly murdered; the whole city took sides; and thenceforward Florence was distracted by the disputes of the rival factions.8

The most fantastic sight of all now appears, a body walking toward them holding its own head in it’s outstretched hand, swinging it like a lantern:

Out of itself it made itself a lamp,

and they were two in one and one in two;

how that can be, He knows who so decrees.

XXVIII.124-126

This sinner lifted up the head close to Dante so they could hear it, calling out the depths of its own suffering. Bertran de Bron was a troubadour, Lord of Hautefort, who played a role in the young Prince Henry’s rebellion against his father, King Henry II of England. The strife of their dynamic is like that of the counselor Achitophel, who encouraged Absalom to rebel against his father King David in the Old Testament.9

By cutting these familial bonds, his just punishment is in this cutting off of his head; the ultimate example of the contrapasso punishment

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

We survive on adversity and perish in ease and comfort.

~ from Livy’s History of Rome, Book II

Each tongue that tried would certainly fall short

because the shallowness of both our speech

and intellect cannot contain so much.(lines 4-6)

The power of speech, the two forms of division, and the origins of Islam—these are the three central themes to reflect upon in the philosophical exercises of this canto.

The power of speech

Tortured, split in half, and mutilated beyond recognition, the damned still attempt to speak - clinging to their most powerful weapon: speech. Even in torment, they seek to sow discord under the guise of unity.

It is the skill of a good cook, says Socrates in the dialogue Gorgias, to make unhealthy food appear pleasant. For the Ancients, actions spoke louder than words: the ethical essence of a speaker came before speech itself. To put it more clearly: one had to prove who they were through their actions first, and only then would their words carry natural persuasive power.

In other words, no matter how masterful a speech may be—how polished, eloquent, or pleasing to the ear—it carries no true weight if it springs from a corrupted character. Words divorced from virtue may dazzle, but they do not become true.

It is worth reminding ourselves that we are now in the ninth bolgia—the realm of the sowers of discord—and the kind of speech we encounter here differs sharply from that of Ulysses and Guido in the previous bolgia, where the evil counsellors spoke with seductive eloquence and calculated reasoning. Here, language is no longer a tool of persuasion but a fractured cry torn from mutilated bodies, a reflection of the division they sowed in life.

The speech that Mohammad and Curio used aimed not at a calculated Machiavellian result, which we explored in the previous canto, but created religious and political discord.

What is the difference between Scandal and Schism? (Two Types of Division)

E tutti li altri che tu vedi qui,

seminator di scandalo e di scisma

fuor vivi, e però son fessi così.…

And all the others here whom you can see

were, when alive, the sowers of dissension

and scandal, and for this they now are split.

Muhammad tells us that those whom our companions encounter in this bolgia are those who sowed schisms and scandals. The former is related to religious division, for which Muhammad is gruesomely punished here, whilst the latter is a political division. But, why scandal? I think we should once again use ‘archaeology of words’ (etymology) to see the meaning that lurks in the shadows here.

The word scandal, so often associated with political division, finds its roots in the Greek skandalon, meaning a “stumbling block” or “snare.” Those who cause scandal do more than merely offend—they lay traps in the path of society, causing its moral and civic foundations to fracture. They sever the roots that bind communities together.

No sinner exemplifies this more vividly than Curio, who urged Julius Caesar to cross the Rubicon, setting in motion a civil war so devastating it would become the central theme of Lucan’s Pharsalia, a work Dante held in high regard.

Muhammad and Ali, however, are depicted as having sown a different and far more profound kind of discord. The division they caused was not merely political or territorial—it was spiritual. Their actions, in Dante’s vision, fractured the very soul of human unity, creating a schism not between nations or rulers, but within the sacred sphere of belief itself.

The Origins of Islam

I can only assume my reader was surprised, as I was once myself, that Dante knew nothing about Odysseus as described by Homer, since at the time of the great Tuscan poet The Odyssey had not yet arrived to the Latin Christendom.

In the same way, it is surprising to discover that Dante, as well as his mentor Brunetto Latini, thought that Mohammed was originally a Christian priest, who chose to preach his own, according to them, heretical religion. In Latini’s Tresor , for example, Mohammed is described as evil priest who intentionally drove Christian believers from the truth to error.

Where do the origins of this belief come from?

I will have to disappoint my reader by telling them that I do not know, but yet, I can point to some sources that a curious mind might use begin their journey.

The first secular source I’d like to draw your attention to is In the Shadow of the Sword by historian Tom Holland, one of my favourite popular historians. In this compelling work, Holland explores the origins of Islam, revealing how the religion gradually took shape over the course of centuries. If you’re short on time or prefer a more accessible entry point, I highly recommend his documentary Islam: The Untold Story, which is freely available online.

For those with a deeper curiosity, I’d suggest the 1971 book Hagarism by Patricia Crone and Michael Cook. This groundbreaking study approaches the early history of Islam through the lens of non-Islamic sources, offering a bold reinterpretation of its formation.

If even the modern historians raise questions and investigate the origins of Islam, it should not come to us as a surprise that Dante and the rest of the medieval tradition could make mistakes in their understanding of who Mohammed was.

Final thoughts

When we first descended into the circles of fraud, I found myself puzzled - why would Dante place seducers so low, while seers and diviners remain relatively high? But as we move deeper into each bolgia, Dante’s moral architecture begins to unveil itself with greater clarity. Each form of fraud is not isolated, but generative. One deceit gives birth to another, and what begins as a subtle misdirection—like that found in the heart of Ulysses - sets the stage for far more catastrophic acts of division, like those attributed to Curio and Mohammed.

It is as if fraud were a spiritual illness: at first minor and perhaps even excusable in appearance, but left untreated, it spreads, metastases, and ultimately destroys the whole organism. The seducer may corrupt an individual, but the divider fractures entire peoples. Dante’s taxonomy of sin becomes a kind of diagnostic chart of the soul - tracing how the smallest betrayal can become the root of the greatest collapse.10

What makes Dante an exceptional genius is that even with fragments of knowledge about Ulysses and others he comes to conclusions the veracity of which were proven by time.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

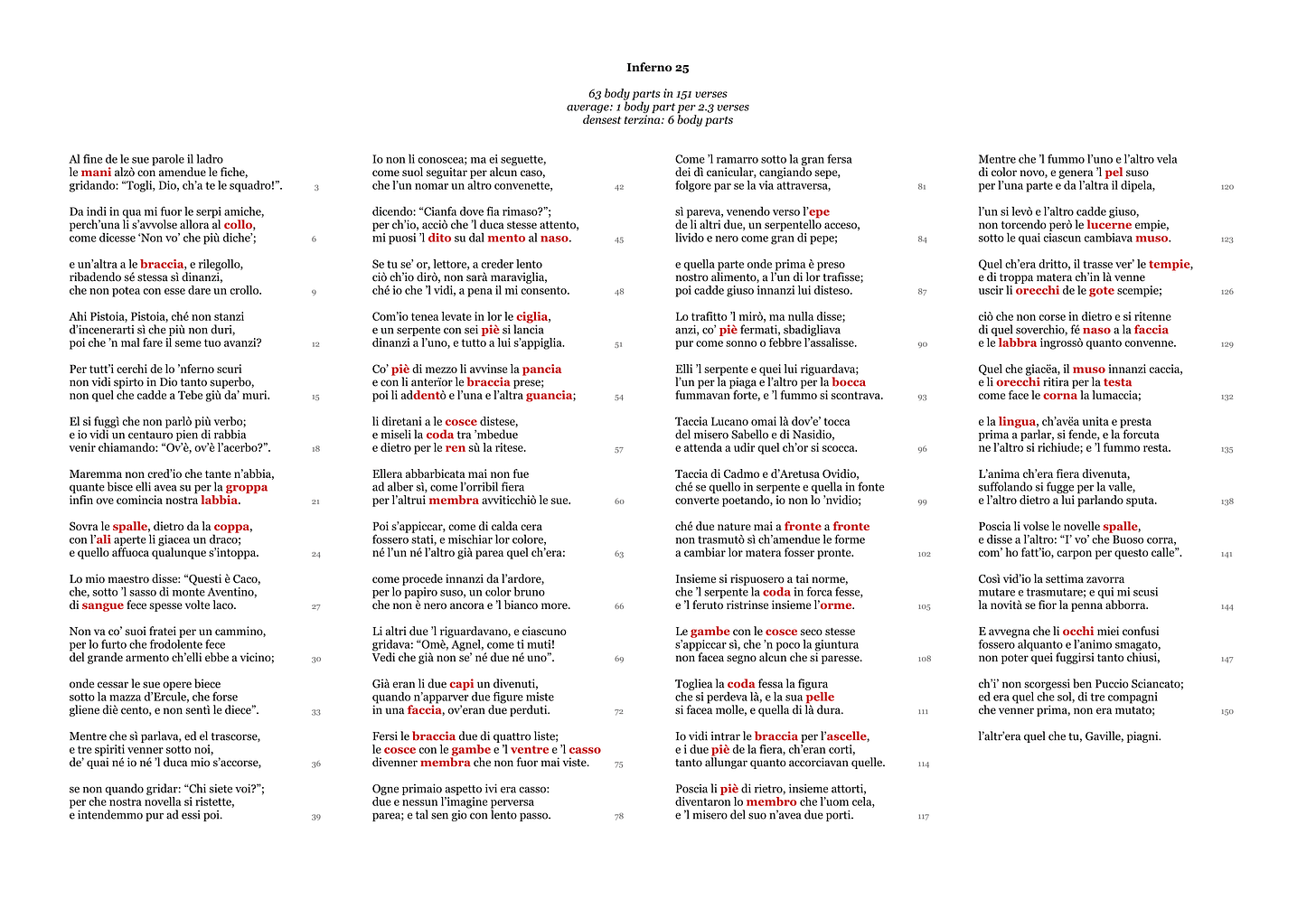

How many mutilated body parts?

Canto 28 takes pride (or, is it the right word?) by the number of body parts mentioned. The first place is taken by Inferno 25 where we see 63, and Inferno 28 has 41.

To calm my reader’s mind, it is not myself who kept “body part count” but Grace Demolino: here’s her calculation:11

Dante copying Livy

Once again, it seems that in each canto-or better yet, in each carefully crafted scene-Dante subtly challenges the style and mastery of his literary heroes. In the canto of the thieves, he rivals Ovid in the art of metamorphosis; earlier, he dared to question Virgil, his own guide and poetic father. And now, though Livy was no poet and does not appear among the great souls in Limbo, Dante takes it upon himself to outdo him as well-showing that the battle scenes and the history of Rome could be told not only with greater drama but with deeper moral clarity.

Unity vs Disunity

For Dante, unity is paramount - both in the political realm and, more subtly, within the soul and the pursuit of knowledge. In the Dantean and Aristotelian worldview, truth is inherently unifying: it draws together disparate elements, harmonises contradictions, and brings order to multiplicity. Falsity, by contrast, fractures. It severs what belongs together, leading to inner dissonance and societal discord. I find this vision deeply moving and profoundly true. It brings to mind another towering work of literature - Paradise Lost by John Milton - where Satan is not only the rebel, but the great divider: he splinters what was whole, drives wedges between angels, and severs humanity from the divine.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

Who, even with untrammeled words and many

attempts at telling, ever could recount

in full the blood and wounds that I now saw?Each tongue that tried would certainly fall short

because the shallowness of both our speech

and intellect cannot contain so much.

Isidore Etym. viii.3, Singleton 505

Livy, Ab Urbe Condita XXIII.xii.1-2

Singleton, Commentary on Inferno 503

Sayers Hell 250

Inf X.100-108

Singleton 512-513

Lucan Pharsalia I.280-281: Curio to Caesar on whether to cross the river.

Sayers Hell 251

II Samuel 15:7ff

https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/inferno/inferno-28/